How many times have we lashed out on our mothers saying ‘aap karte hi kya ho ghar pe? Khana hi to banate ho’ (what do you do all day? You only cook meals) when we come back dreaded from our work; ignorant that what she does is also ‘work’, just that she does not get paid for it? How

often have we seen our sisters/female friends being told ‘padhkar kya hi karegi? Shaadi ke baad bacche hi to sambhaalne hai’ (why do you need to study, when you have to take care of kids after your marriage), synonymizing women with caretakers? Such societal perceptions of women’s role have held them from rising and paved the way for magnified gender discrimination. For instance: in India, women held only 28 per cent of managerial positions worldwide (UN, 2020). Further, only 25% of women represent national parliaments globally (UN, 2020), a minuscule increase

from 24% in 2018 (UN, 2020).

Excluding half of the world’s population (World Bank, 2019) from equal opportunities not only violates a fundamental human right but is a form of widespread injustice. To address this issue, the United Nations committed to eliminating all forms of discrimination and violence against women by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). The good news is that we have marked some tangible progress on it as, two countries have women Prime Ministers (O’Neill, 2021), period products are made free of charge in New Zealand (BBC, 2020), non-consensual sex is legalized as rape (The Week, 2020), pregnant girls are now allowed to attend schools in Tanzania, and Sierra Leone (BBC, 2020), and Sudan has banned female genital mutilation (BBC, 2020) amongst others. These examples portray we have come a long way in providing equal opportunities to men and women.

However, there is little to rejoice! Estimates suggest that the global gender gap (which accounts for economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment) will close in 100 long years, on an average [1]. Gender gap amongst the

ultra-wealthy is widening each year, where hardly 12 women are amongst the top 100 billionaires(Forbes, 2020). More so, poverty in developing countries is ‘gendered’, [3], which means men and women experience poverty unequally.

Although ‘gender discrimination and gender inequality’ is a multi-faceted area, this article focuses only on the aspect of ‘unpaid care economy’.

Need to Care About the Care Economy

Care economy is a system which includes activities to fulfil the emotional, physical, and psychological aspects of care, primarily for family members. It being statistically invisible, does not monetize the efforts of care workers. Across the world, without exception, the care economy employs the majority of women. 76.2% [4] of the total time devoted to unpaid work (collectively 16.4 billion hours every day (ILO, 2018)) is done by women, while men devote less than a quarter of this figure. A man spends only 83 minutes per day on unpaid work – which is barely 33% of 256 minutes spent by a woman [5]. Globally, women and girls from marginalized communities put 12.5 billion hours [8] every day of care work for free. Investing time in the care economy poses a trade-off against investing their time in paid work, which means they get lesser time to participate

in the labour market meaningfully.

I have yet to hear a man ask for advice on how to combine marriage and a career!

- Gloria Steinem – an American feminist and journalist

This quote perfectly reveals the essence of ‘time poverty’ – shortage of time available to devote purely to leisure. Women face significantly higher time poverty than men [9]. It not only discourages them from participating in the labour market, but leaves them with less time for

themselves, making them mentally, emotionally, and physically exhaustive. Furthermore, they are more likely to withdraw from labour-force as they are charged with ‘motherhood penalty’ of taking care of their kids because of the muted patriarchal norms of ‘male being a breadwinner’. Of the global pool of labour-force, only 48.5% [10] women participate in contrast to 75% men.

Problem is not just the statistical invisibility of care economy, but the deeply ingrained patriarchal norms that have repercussions on economic growth. However, economy-wide effects can be partially muted if the care economy is perfectly integrated into every nation’s development agenda, as suggested by Diane Elson.

Make Development Equitable

Diane Elson suggests that we must include ‘Triple R Framework’ (Recognition, Reduction, and Redistribution) of care economy in our policy memorandum to ‘reduce the burden of care economy

on women girls’.

Recognition

Recognizing the length and breadth of the care economy is imperative to make the contribution of careers visible. This is done using time-use surveys where qualitative and quantitative information of the scope of unpaid work, its burden, and distribution is captured. These surveys help in removing the ‘statistical invisibility’ of the care economy. Besides this, gender-responsive budgeting, specifically, benefit incidence analysis is a brilliant method to capture the actual benefits of women-centric policies so implemented to reduce care burden.

Reduction

Investment in labour-saving technology will reduce ‘time poverty’ – a concept where women cannot devote less time to paid work due to the burden of unpaid work. Investments in day-care centres, creches, or similar care-burden-reducing-infrastructure can contribute here positively.Investments in better housing, water, and sanitation facilities, fuel-saving stoves reduce burden[12] on women are some other areas we need to focus on.

Redistribution

Redistributing responsibilities, time, and resources of care work between man and woman of the household will ensure equity in distributing care services. Equal parental leaves are the most significant contributor to this. Community programs also help create awareness about redistributing the care work, even if it does not involve parenting per se.

Policy Recommendations

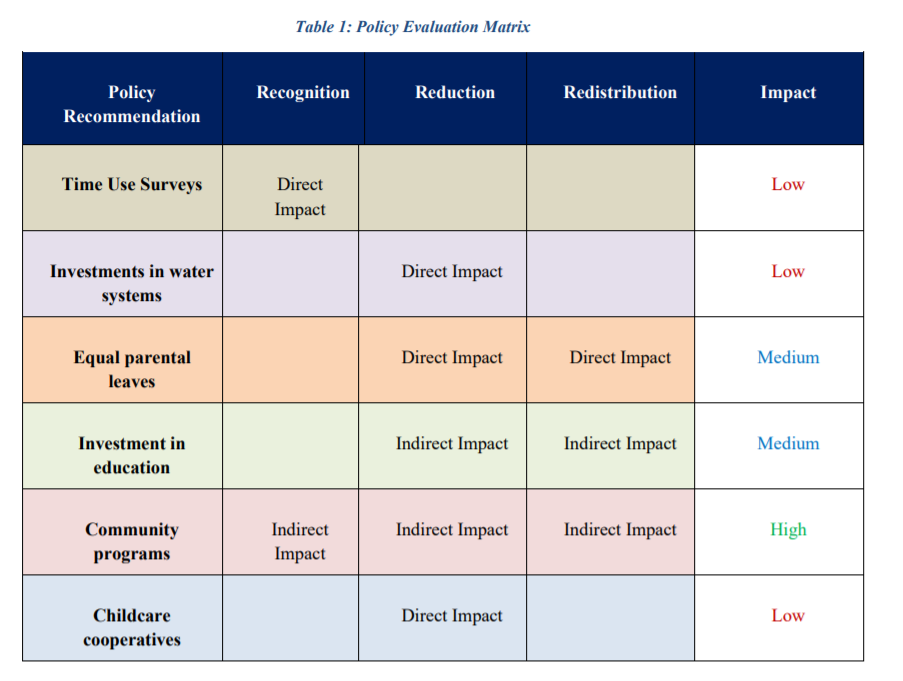

It is essential to have policies in place, but how do they impact the ‘Rs’ of care economy should be of prime importance, for which below is a policy evaluation matrix (Table 1) [13]. It justifies how each of the policy recommendations affect the care economy in recognizing, reducing and

redistributing the ‘care burden’ in the society.

I recommend policies in order of impact, i.e., high impact policies (all three Rs being impacted) should be chosen over medium impact policies (only two Rs being impacted), followed by low impact policies (only 1 R being impacted).

- I describe the policy recommendations in brief below:

- Time use surveys directly recognize the care economy by directly measuring how much time is being spent by care workers (primarily women) on care work vs paid work. However, this is a low impact policy as it impacts only 1 ‘R’ (i.e. recognition).

- Investments in water systems: efforts geared towards improving water infrastructure (e.g. piped water) can directly reduce the ‘water’ burden on women[14], which can further reduce ‘caregiving’ burden on women. As of 2016, women around the world collectively spend 200 million hours collecting water[15]. Policies like Jal Jeewan Mission will help provide piped water to each house, thus reducing the burden of water collection. However, this is a low impact policy as it impacts only one ‘R’ (i.e. reduction).

- Equal parental leaves: equal paternity leaves are a far-fetched policy recommendation in a world where only a handful [16] of countries provide parental leaves. Japan is the only country which provides generous paternal leave (of 30 weeks as against 36 weeks of maternity leave), but only 5.14% fathers take this leave (OECD 2016). Therefore, a policy recommendation should not just give equal parental leaves to both the parents, but also ensure men do avail it. This will directly reduce and redistribute the care burden as the couple would be able to invest an equal amount of time in child-raising, instead of the woman being the sole caretaker. This, therefore, forms a medium impact policy as it affects both the reduction and redistribution of the care economy.

- Investment in education: girls in rural areas often have to forego their school to collect water, feed the animals, or do household chores. In such a case, they feel disengaged and are likely to consider dropping out of schools [17]. Thus, one of the investment could be that night schools could be an excellent way to recognize care workers. Think of it in this way – what if 100% of attendees in night schools are girls that means all boys go to day schools, and girls are engaged in other care activities, making it easy to recognize the ‘care-givers’. Another policy recommendation would be to give scholarships or cycles to children, encouraging them to go to schools. More so, educated boys (and girls) better understand the nuances of ‘care economy’, which might indirectly

help in recognition and redistribution of the ‘care burden’ within their family. - Community programs which focus on gender sensitization activities for young boys and girls should be encouraged. Activities involving children to recall their parents’ responsibilities and categorizing them into paid and unpaid work will allow children to recognize their mothers’ work

as part of the ‘care economy’. Programs involving boys in ‘demonstrative activities that involve them to do household chores can reduce and redistribute women and girls’ burden. Community programs are a ‘high impact’ policy recommendation that covers all 3 Rs of the framework. - Childcare cooperatives – creating day-care centres, creche, and childcare provision at workplaces will reduce the burden of childcare on working women. This is a low impact policy as it affects only the ‘reduction’ of the care economy.

As the above policies recommend, community programs can have a high impact on understanding the nuances of the care economy for developing a country. Nonetheless, it remains indisputable that the care economy is an important issue to deal with, and ignoring it for long will only delay the ‘closing of gender gap’. Gender impact evaluations, for instance, are a definite positive step for integrating the ‘Triple R Framework’ in the development agenda of a nation. Further, all policy recommendations hold little substance unless patriarchal thinking gives way to progressive outlook towards women.

End Notes

[1] Global Gender Gap Report 2020, World Economic Forum

[2] Ibid 1

[3] Addressing Gender Concerns in India’s Urban Renewal Mission, Renu Khosla, UNDP, India

[4] Care Work and Care Jobs – for the future of decent work, ILO 2018

[5] Ibid 4

[6] Ibid 4

[7] Ibid 4

[8] Time to Care – Unpaid and Underpaid Care Work and the Global Inequality Crisis, Oxfam briefing

Paper, January 2020

[9] Chapter 1: Women and Poverty; Global Women’s Issues: Women in the World Today

[10] International Labour Organisation, March 2018

[11] Time to Care, India, Oxfam India 2020

[12] Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link In the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes, OECD,

2014

[13] This was taught to me as a part of the curriculum for 16-days Public Policy Bootcamp organized by

Vision India Foundation, June 2020

[14] Gender, Water and Sanitation: a Policy Brief, UN Water (2000-2015)

[15] Women and Water: A Women’s Crisis, Jennifer Schorsch, Water.org, 2016

[16] Are the world’s richest countries family friendly – Policy in the OECD and EU, UNICEF, June 2019

[17] Students’ paid and unpaid work, OECD 2017, PISA 2015 Results (Volume-III)

Komal is presently working as a research associate at NEERMAN, a research and consulting firm based in Mumbai. Prior to joining NEERMAN, she interned at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, a think-tank based in New Delhi, focusing on studies that relate to gender budgeting.

She has completed her Masters’ in Economics from Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and has majored in Economics from the University of Delhi.