How we make a choice tells us a lot about us, than the choice actually made. Being able to choose is also a luxury since making a choice is an act of exercising both freedom and power and makes one feel empowered, rarely recognizing the price we pay. Today policymakers are being trained to think like economists, a big part of their training is to estimate the ‘Opportunity Cost’ which is the coast of not choosing the next best alternative to the available money, resources, time, etc.

So, it’s safe to say that decision makers make trade-offs on a daily basis. Turns out, mostly these choices are mutually exclusive. For everything selected, the next best alternative is forfeited along with its concomitant benefits. But, does letting go of the next potential option seem like a loss? Maybe not, since the selection is an assertion of one’s free will and rationality.

Voting is the fundamental concept of any democratic structure. Who gets to vote and why, on what issues and for who form the premise of what social scientists interested in voting and democracy study today. There are complex questions with no definitive answer but interestingly hold one common string – the process of how people exercise and cast their vote. An individual’s right to vote ties one to a social order in return giving them a collective and shared belief even if one chooses not to vote. Public Choice Theorists termed it as ‘Rational Ignorance’ since voting is a right not a duty. Either way, voting is the beginning, everything else in democracy flows from it.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that this core tenet of democracy has been of great interest. Condorcet, an eighteenth-century French philosopher and mathematician in his essay ‘Application of Analysis to the Probability of Majority Decisions’ of many other things studied the rules of voting and theorized ‘Condorcet method’ that stated electing a candidate who beats all other candidates in pairwise elections. By design, electoral institutions help us understand the implications of incentives on the behavior of individuals.

Democracies need to evolve both to cater to the needs of citizens and meet demands of the new generations. In this regard, India has been debating over the issue of Proportional Representation (PR) versus First – Past – The – Post (FPTP) for decades. Why is this debate telling and pivotal? In this article, we take our readers through the analysis of the Indian Electoral system and let the final conclusion make its way through the readers’ mind.

ELECTORAL VOTING SYSTEMS

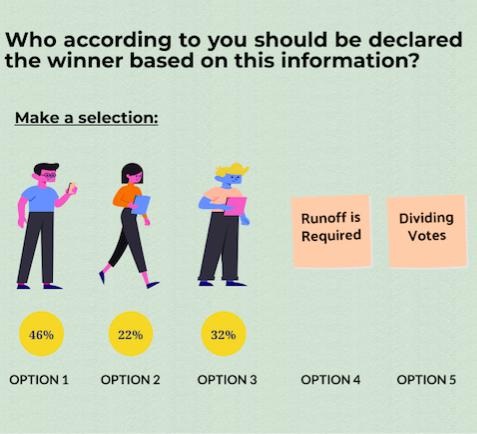

Before we present an argument to replace India’s current FPTP with the Proportional Representation Electoral System, let’s play a small game before we move ahead and present our case.

- Option 1: You prefer the Plurality method/ First – Past – The – Post or Winner takes it allmethod. A legacy of the British colonialism, the system rewards the entity with majority, irrespective of how small the majority is. What it means is that even if 80% of the constituency voted against a candidate, the candidate will still be the winner since no other candidate got more than 20% of the polled votes. So, the catch here is that instead of being the preferred choice of the majority of electors one only needs to target specific voter segments (~vote bank politics) to win an election.

- Option 2: No voting system will support this candidate to win.

- Option 3: No voting system will support this candidate to win.

- Option 4: You chose the alternative voting or instant run-off method. Voters can rank formultiple candidates in order of preference. The counting starts gauging the top choice of each voter. That is, if a candidate is the first – choice of more than half of the people who voted, the candidate is declared the winner. If not, the candidate with the lowest number of votes gets eliminated, and the process is repeated again. In effect, voters subsequently rank multiple candidates from most favorite to least favorite until one person crosses the 50% (majority) mark.

- Option 5: You prefer the Proportional Method that involves votes being proportionallydistributed amongst all the candidates contesting the election. This method provides wider representation in our legislature to all political groups, which is the foundation of any democracy. This method ensures that the seats won by any political party is proportional to the votes polled, providing representation to minority groups unlike FTFP that only depends on a majority. For example, in our case, the candidate that earned 46% of the votes would have 46% of the total seats in the assembly house. Similarly, the candidate that earned 32% of the votes would have 32% of the total seats and so on.

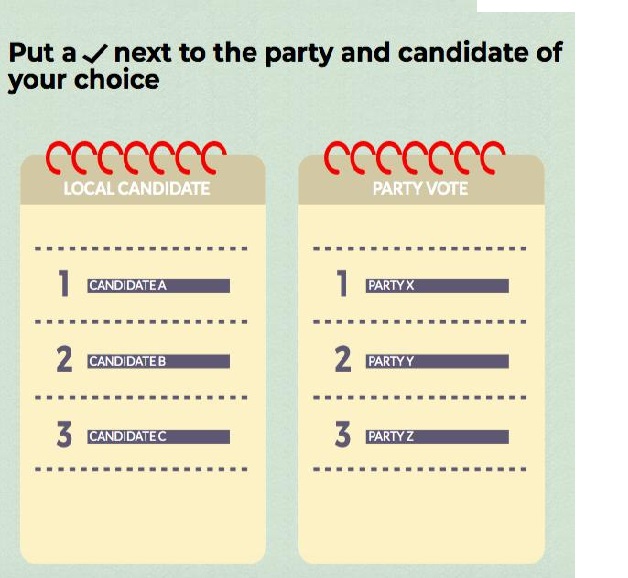

There are primarily three types of PR Voting Methods – Single Transferable Vote (STV), Party List (PR) and Mixed – Member Proportional Representation (MMP). As per the electoral system experts, MMP is the preferred choice for voting which gives voters two votes, one to

elect a representative for their respective constituency and other one for the overall political party. This is how it would look like:

SWITCHING TO PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION VOTING SYSTEM

Using our example, we see that the interests and votes of 54% (22+32) people who vote against the winner (majority) are completely neglected. So, it goes without saying that the winning candidate is focused on catering to the needs and demands of people who voted for them. There is a tacit compulsion on the winner to look for a niche (~establish a niche vote bank) to safeguard their seats for a re-election. Hence, under our current FPTP system, a candidate will still be declared the winner even if the majority of the people in the constituency vote against them.

We argue that the Proportional Representation system by design encapsulates socio – economic and diverse political views making it far more inclusive than all other available options. Having elements of FPTP, it is unique in the sense that it overcomes its anomalies by creating a representative body formed on virtue of diversity rather than popularity.

To put this in perspective, in the 2018 Madhya Pradesh elections, despite winning 47,827 votes more than the Congress and having a 0.1% more vote share, BJP had only 109 seats compared to 114 of Congress and lost the election. For similar reasons, the parliamentary election results of 2014 were much debated wherein BJP with 31% of the total votes was successful in forming the government.

In a PR voting system, any voter exercises two votes – one for the candidate and the other for the party. It picks the winning candidate as per the FPTP system, meaning anyone who has the majority number of votes wins. Let’s say that number is 45%. Then the rest 55% will be divided between all the political parties contesting based on the percentage of votes received in their constituencies, states or across the nation.

Therefore, like many others, we believe it’s time for India to take the plunge and move towards a Proportional Voting System.

This article has been co-authored by Sanyukta Sharma, Raghav Jhunjhunwala and Aranya Sharm. Raghav and Aranya are students at Delhi University.

Sanyukta works on Public Policy & Communication Strategy with Chief Minister's Office, Government of Haryana. Earlier she was a research associate with IIM Ahmedabad, Chief Minister's Good Governance Associate and Project Associate - Health and Social Policy, Harvard Project for Asian & International Relations.