The year of 2018 ended calamitously as a crucial Non-banking Financial Company (NBFC) defaulted on its payments. It was infamously dubbed as India’s Lehman moment. The fall of Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (ILFS) triggered a chain reaction of defaults in the sector due to many companies’ Asset Liability Management (ALM) concerns. The wound of systemic vulnerabilities continues to remain unattended as the impact of illiquidity has eroded trust in the system. The mismanagement’s chief observer – Reserve Bank of India (RBI) – sequentially cut rates with the hope of reviving liquidity. The haphazard implementation of the Goods and Services Taxes (GST) and a nation-wide demonetization parade further created a setback derailing the economy. In this backdrop, the need for an analysis of the curb of liquidity – primarily defined as the ease of conversion of assets into cash – is needed to assess the opportunity forgone in rendering growth and development.

Rundown of the situation

It has been suggested in the past that the key to resolving this distress is by improving governance mechanisms in companies, and regulation standards of the statutory authority. A policy shift can be deployed wherein the institutions are ‘nudged’ towards imbibing these changes. Below are the two conditions, and their consequent implications, persistent in the Indian economy:

1. Boosting real factor growth: The real factors of growth – investment in R&D, human capital, seamless taxation, labor and land laws, clean and efficient energy, and honing manufacturing capabilities – seek reinforcement by a country’s financial sector conditions. Capital unavailability due to high-cost can erode infrastructural or other productive developments in an economy. Ben Bernanke is right to say that the premium paid on external borrowing is inversely proportional to the firm’s balance sheet’s strength – a greater premium to be paid if the borrower is financially incompetent. Hence, the ‘financial accelerator’ works when external premiums are low and accelerate the impact of real factors of growth, inducing productivity. The Economic Survey of 2019 focuses on the need to shift towards a virtuous cycle of growth through plugging of essential gaps of output in the real-factor economy. This is possible only if our financial sector has enough liquidity to create the necessary demand.

2. Revenue and government schemes: When a country hits a downturn of such severity, eyes are upon the government to increase spending. It was the first time that the government incorporated the method of the “Outcome Output Framework” of spending which improves efficiency in delivering specific targets of major Central Sector Schemes and Centrally Sponsored Schemes. Although the revenues from GST crossed the Rs.1 lac crore mark in November hinting a degree of revival in consumption, the channel of disinvestment seems to be the government’s key operating tool to address the expenditure challenge without transgressing upon the fiscal deficit.

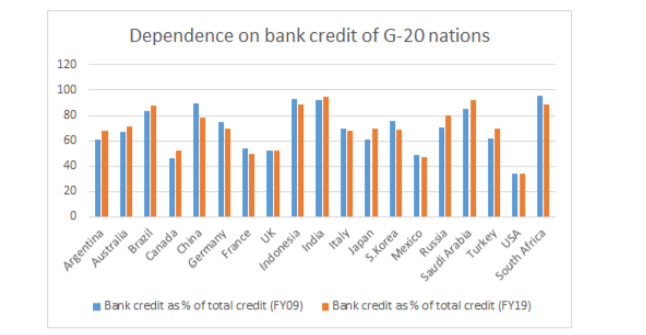

Despite the 135 bps cuts this year, the rates at which Non-banking Finance Companies (NBFCs) take credit are burdened with high-risk premiums, resulting in an unfavorable financial accelerator for the sector. NBFCs have played a crucial role in securing credit growth – 9.6% greater than credit created by banks in 2018. The slowdown in automobile sales stemmed from the role NBFCs played in funding 55-60% commercial vehicles, 65% of two-wheelers, and nearly 30% of passenger cars. It is known that the private sector will only provide investment for infrastructure if it is a profitable venture. Constrained by liquidity, debt, tax terrorism, and overcapacity, the public investment in infrastructure does not give its private counterpart enough space to co-invest – exacerbating the woes of financial firms and challenging its competencies to finance crucial investment. Furthermore, at the beginning of 2018, the rural economy began showing signs of distress. The shift from agriculture to construction jobs led to falling wages due to the ailing infrastructure sector which was chiefly financed by NBFCs. The real-estate developers sourced as much as 100% incremental credit from NBFCs in 2018 (almost 70% urban construction is commercial and residential real estate). Hence, the key to understanding the crisis is by acknowledging India’s dependence on credit from banks. As highlighted in an ORF analysis, banks are highly susceptible to feel the pinch by a liquidity deficit in the system as their exposure by lending to NBFCs invested in infrastructure projects – now turned into bad loans – has increased the stress on the primary source of credit creators of Indian economy.

Concerns of the past coming to light

Past insights give us a direction to resolve the current situation:

1. The stress on the balance sheets of NBFCs and banks due to their exposure to infrastructure and housing projects has renewed enthusiasm to embrace Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). Major DFIs of the past joined their banking peers (such as ICICI and IDBI), and others were reclassified as NBFCs. An RBI working paper in 2017 accorded the need to revive the space for long term and wholesale banking. This recommendation was based on the premise of the bank’s ability to harness their “core competencies” and in turn reduce intermediation costs and improve the allocation of capital. The effort on this front was realized recently when the FM announced the creation of an institution as such to fund infrastructure projects.

2. An RBI report in December 2017 mentioned that shadow banks in India had 99.7% loans provisioned on short-term funding – one of five crucial economic functions of an NBFC, as against the global dependence of mere 8%. Another one of its working papers in 2011, while commending NBFCs for their instrumental success in making credit and other financial services easily available, highlighted that NBFCs’ (both deposit and non-deposit taking) consolidated balance sheets constituted 68% borrowings out of which 30% was that of banks and other financial institutions. Another 33% of these borrowings were issued by way of debentures which were mostly subscribed by banks. The plausible implication should have been to raise stringency on NBFCs regulation after having assessed the “systemic vulnerabilities” of such interconnectedness which played out during the crisis of 2008.

3. Former Dy. Governor Usha Thorat in her committee report on Issues and Concerns on NBFCs, highlighted some key guidelines for liquidity management, corporate governance, disclosures, and other recommendations specific to categories of NBFCs which are critical to the structure and functioning of the sector.

4. The Financial Sector Board, constituted in 2009 comprising of the G20 nations, was created to bring about regulatory and supervisory changes ensuring financial stability. Following its guidelines, India’s performance compared to its peer nations has not been at par:

a. India has persistently flouted the norm to reduce interdependencies between banks and NBFCs: Rising from 92.5% in 2009 to 94.4% in 2019, Indian NBFCs have grown to have the largest component of borrowings from banks in their books compared to the G-20 nations.

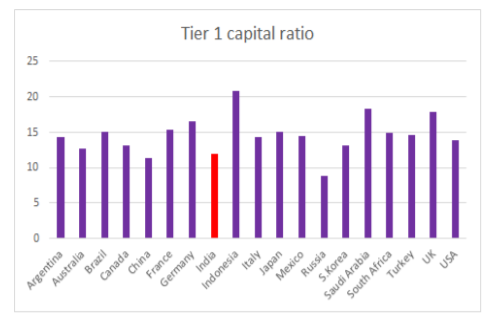

b. The ability of a bank to absorb losses on its capital is compromised when its Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) is low. India, amongst its G-20 peers, falls on the lower side of the ratio as a proportion to risky assets.

India is clouded by dismal economic indicators raising doubts over the government’s vision to reach a $5 trillion economy by 2024-25. This recessionary environment – aided by a crunch of liquidity in the system – disables the dream of a buoyant economy alongside the government’s crucial political ambitions. Modi 2.0 government may have unwittingly inherited from its previous tenure a formidable economic challenge that it did not foresee.

Tanya Rana is a student at Anil Surendra Modi School of Commerce, NMIMS, Mumbai. Previously she has worked with Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Observer Research Foundation and was a delegate to Harvard US-India Initiative Conference 2020.

Superbly analysed and written. Congrats to the writer for the study n the article.

What a fantastic insight this author has given about the state of economy and how bringing back the liquidity is so important.

The analysis of causes and factors which brings upon the downward trend of economical health is appreciable.

All the best!!