If one has to pick an Indian equivalent of USA’s 2007-08 national banking emergency ‘subprime mortgage crisis’ it would definitely be the biggest component of targeted or priority sector lending programme: Agricultural Credit. Although the share of agriculture in Gross Bank Credit(GBC) in India at present is not as high as the share of credit backed by Mortgage Backed Securities and Collateralized Debt Obligations in USA in 2007. As per the RBI’s latest Gross Credit Deployment Report(May 2018) agriculture and allied activities accounts for only 13.5 percent of GBC. But the quality of assets and underlying economic philosophy tell a story similar to American Housing Bubble in early and mid-2000s.

Asset Quality Paradox

When in January this year RBI Governor Urjit Patel cautioned against farm loan waiver schemes by state governments as it creates pressure on finances of both government and lenders; a former PSB CEO questioned his wisdom by saying, “corporates defaulted on repayments, destroyed credit discipline and culture. Why should farmers be blamed?” Upto an extent this is true. As of 2017 Industry and Infrastructure sectors constituted for 76.7 percent of total NPAs and defaulted 20.8 percent credit whereas farmers defaulted only 6 percent of credit supplied to them. But rising demands for farm loan waivers by farmer pressure groups across the states and ever rising number of farmer suicides contradict fidelity of this number. There may be several reasons for lower recognition of agriculture NPAs. Most of farm loans are sanctioned at branch office level so in case of a possible default they are easily ‘restructured’ again and again. My experience as a rural banker suggest that it is a widely prevalent practice across the banks to keep NPA levels under check. Second, penal cost of default for farmers is much higher than industry as they would immediately lose interest subvention benefit and whatever insurance cover they have. So even in situations of stress they tend to borrow from relatives, moneylenders or most probably from commission agents at exorbitant interest rates of 24, 36 percent or more to service interest of debt. So a Non Performing Asset now becomes a Debt Trapped Asset.

The most important aspect in this game is practice of ‘rollover’. A Kisan Credit Card(KCC- the scheme under which most of the agricultural credit is disbursed) as a cash credit limit is different from a commercial cash credit/overdraft limit in the respect that in case of later a borrower just has to pay interest and charges on monthly basis and account remains standard. But in case of KCC the farmer has to repay the whole interest plus principle amount after each harvest(generally six months), then only accounts remain standard and farmer is eligible for interest subvention. They are eligible to draw the whole cash credit limit on the same day. Usually farmers repay only accrued interest and two credit and debit transactions of equal amount would do the work. So debt load of the farmers remain constant over the years and they keep on paying interest for years. In theory KCC is a production limit, that is credit provided for working capital requirement in course of production of crops. So the farmers should be able to repay that amount after harvest, which they are not able to. Why they are unable to repay is something we are going to discuss in ensuing paragraphs.

So stable asset quality in agricultural credit is a myth.

Underlying Economic Philosophy of Agricultural Credit in India

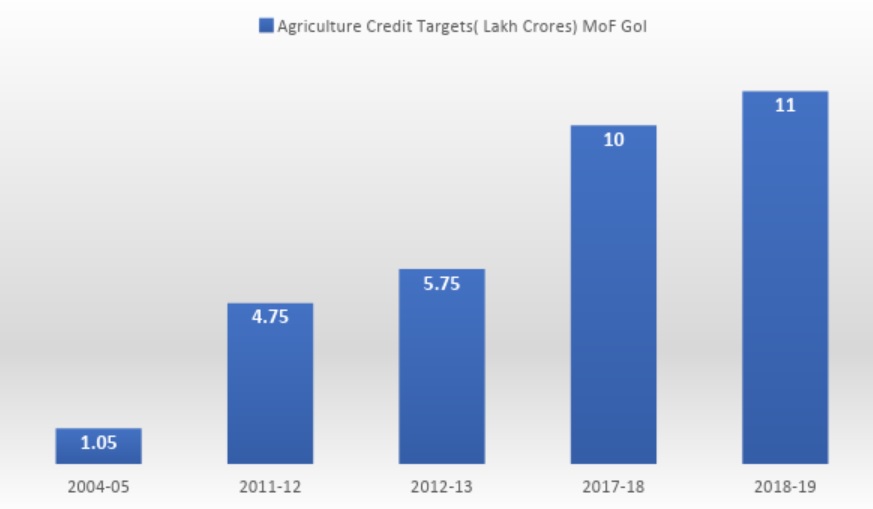

Union budget 2018-19 announced raising institutional credit for agriculture to 11 lakh crores from 10 lakh crores in 2017-18. Increasing institutional credit every year or alternate year by 10 percent has been the practice for at least last two decades. So why does government want to supply more debt to an already debt-ridden sector?

I find two reasons behind this irony. First is the simplistic reason that additional 10 percent credit can easily cover the interest part(which is more or less of similar magnitude) and banks can easily ‘restructure’ or ‘rollover’ the KCCs without expecting farmers to repay at least interest part. Philosophy part is in the second reason.

During my close interaction with unsecured and secured farm and non-farm borrowers one issue that came to forefront was that a significant portion of this credit expansion went to consumption purposes instead of productive activities. So upto a good extent this confirms the fears of ‘Consumption Smoothing’ raised against Gramin Bank in Bangladesh founded by Muhammad Yunus. As Raghuram G. Rajan(2010) has rightly concluded that in the absence of easy solution to reduce income inequality there was a political focus on reducing consumption inequality which included boosting access to credit. Interestingly this is true for both developed economies(subprime crisis in USA) and developing economies(agricultural credit expansion in India). Whether this was a deliberate policy or unintended fallout of a well-meaning policy; remains to be investigated enough.

Circumstantial evidences suggest that it has been a deliberate policy both in developed and developing economies. Political fallout of inequality can be dangerous in a democratic polity. So establishments in countries like USA and India try to raise consumption by poorer sections by providing easy credit. That is why even if farmers with decent landholdings do not have income comparable to urban-middle class they continue to enjoy similar living standards. They own cars and kothis and spend generously on marriages only because of easy access to credit. This serves the purpose of them not realising income inequality.

What is exactly wrong with India’s agricultural credit policy?

No discussion about agricultural credit is complete without discussing the flagship KCC scheme. Launched in 1998, KCC scheme increased farmers’ access to institutional credit drastically. As we have discussed it is a cash credit limit(CCL) with certain variations. Another important aspect is that all working capital cash credit limits are backed by stock as primary security which in case of KCC is crops. But while a non-farm sector CCL need not to be backed by collateral or secondary security upto Rs ten lakhs, a KCC even of Rs one lakh has to be secured by land as collateral. In fact value of land is used to decide size of KCC and not the value of stock(Crops) as in commercial CCLs. So practically a KCC can be repaid only by selling land and not crops. As farmers need money for consumption and banks want to expand their portfolio they inflate production cost so that a higher CCL can be sanctioned. I don’t know people up in hierarchy agree with this policy or banks(or RBI) simply adopted this practice of mortgaging land from their predecessors: the moneylenders.

Now because loan is backed by real estate banks really don’t care about protecting the stock(crop). They simply debit the crop insurance amount from borrower and remit the amount to Insurance Companies. This aggravates the situation as Interest coverage of most farm units is already very weak, in case of a crop failure it deteriorates further and debt accumulation begins.

This situation is dangerous in two ways. First it weakens private property rights in land, which farmers of this country takes vary seriously as a matter of honour. Second if there is sudden focus of banks on cash recovery then price of land may fall sharply and this holds potential of threatening stability of whole financial system. This is where it becomes subprime like situation.

What can be done?

Loan waivers are totally ineffective in such a situation because farmers tend to borrow the same amount again. To right size the inflated ‘production limits’ a portion has to be repaid by famers in one go which they can’t. So as an alternate that portion can be converted into a term loan to be repaid over a period of time like 5 to 7 years. A similar condition was announced by RBI recently for MSME cash overdrafts. This may drain liquidity from rural areas in short run but will effectively cure agrarian crisis without any major hiccups.

We can’t dispute Schumpeter’s conjecture(quoted in Gol’s Economic Survey 2011-12) that Financial Development(of which credit is most important component) facilitates real economic growth. Joseph A Schumpeter wrote in the Theory of Economic Development(1911) that Financial Intermediaries play a pivotal role in economic development because they chose which firms get to use society’s savings. But I tried to relate gap between desired outcomes and these realities of Indian agriculture by analysing different levels of social, economic and financial development in various economies, close interaction among which creates an illusion of universality of applicable principles. Raghuram G Rajan and Luigi Zingales (1998) stress that industries that depend more on external financing grows faster in countries with higher level of financial development. In economies with lower level of social and financial development indicators expanded credit may mainly go to consumption. Social development, financial literacy and discipline have a definite relationship with rational behaviour of actors, which should not be ignored by policymakers in their push towards financial expansion.

Founder.