Every crisis gives birth to its own unique challenges and also opens the gates for new opportunities that alter the way we live, conduct business, and politics. While much has been said about the impact of COVID-19 on individual rights, there is little discussion how a health emergency will paint the spectrum of crime and criminology.

Utilising the investigations into the economic impact of coronavirus in India, this article will focus on the likelihood of increasing the occurrence of crimes of necessity.

Motives of Crime

There have been various studies in the past that link recessions, unemployment, and crime rates. Ross Colvin in his 2009 report in Reuters reported 44 percent of the police agencies reported a rise in certain types of crime they attributed to the United States’ worst economic and financial crisis in decades. The relationship between unemployment and crime rates tend to find statistically significant correlations between unemployment and the property crime rate. Helen Warrell and Andrew Bounds asserted the fact that in the UK, shoplifting, and muggings showed a rise in recession-related crimes as government spending is low and real wages fall. They noticed a 4 percent increase in shoplifting and a 7 percent increase in ‘theft from the person’.

Richard McCleary, professor of criminology at the University of California-Irvine, mentions that “crime depends on three things: opportunity, motivation, and the absence of a capable guardian.” Due to lockdown, the opportunity for crime in India right now has declined tremendously: the latest estimates from Delhi Police show a 42 percent decline in crime since 15 March 2020. In Kerala thefts during the lockdown period came down to two from 12 as compared to the same period the previous year. However, once the lockdown lifts, daily wage earners, deprived of their source of income, may turn to crime for their survival.

Repercussions of Economic Underperformance

Every pandemic is unique, which makes predicting the repercussions of any crisis more educated guesswork than science. While the economic impact of a given pandemic may not be long-lasting if the underlying cause is contained quickly, the vast spread of COVID-19 means the country is likely in for a more protracted downturn.

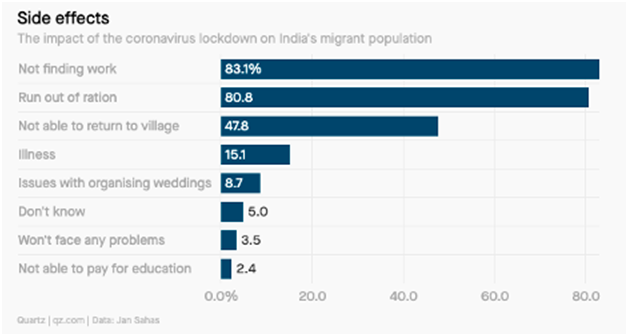

According to a rapid assessment survey by Jan Sahas, as many as 92.5 percent of labourers have already lost one to three weeks of work out of 3,196 migrants workers it surveyed across northern and central India between 27 March 2020 and 29 March 2020. They also worry about not being able to find work post lockdown. While the Indian government has tried alleviating the pain of the migrants during the pandemic with INR 1.7 lakh crore package, most of the workers will be excluded from the relief.

In the absence of reliable data, it may be tough to number them exactly, but not identify those whose livelihood would have been seriously jeopardised because of the lockdown. They include landless agricultural labourers, petty traders, tailors, barbers, construction workers, and rickshaw/auto drivers. As per the All India Manufactures Organisations, about a quarter of over 75 million MSMEs in India that provide employment to over 114 million people are at the risk of facing closure. Mass closure of labour-intensive MSMEs will, in turn, result in the closure of livelihood of millions of migrant labour who specifically work in small factories. The absence of social service nets such as provident funds, gratuity, or insurance will further worsen the situation for these workers. Moreover, new directives of the government for maintaining strict COVID-19 preventive measures while reopening industries will prevent factory owners to employ workers in full capacity. Increasing pressure to comply with such rulings may, in turn, engender increasing pressure on companies to employ irregular or undeclared labour. Organised crime groups can benefit from this by providing irregular workers to otherwise legal enterprises or by exploiting such workers more directly in the production of cheaper goods or services. This issue is closely related to the problem of the smuggling of illegal immigrants and human trafficking. The cost-cutting and tax avoidance by enterprises may pave the way for the expansion of the black market and shadow economy. Markets for counterfeit or smuggled products may broaden, in a possible attempt by operators to maintain levels of consumption or profit in a situation where less purchasing power is available.

Positive correlation between unemployment and crime

The combination of frustration, need to find a quick fix to income loss, and hence poverty due to lockdown may serve as the motivation to turn to unlawful means of income generation. According to a 2018 study by Ugarthi Shankalia and M. Kannappan, as the rate of unemployment and poverty soar in the economy, the crime rate starts taking an upward trajectory. The migrants, daily wage earners, and labourers may find difficult to find work again immediately due to an economic slowdown in the country. The old adage of ‘hunger makes a thief of any man’ will have high probability to see the light of the day. The idea is that these desperate people will storm food stores or break into homes of the wealthy for the want of their survival. Smaller firms and establishments seem to be more exposed to fake invoices, racketeering, theft, and shoplifting. The inability to obtain employment or maintain basic standard of living may result in frustration and emotional stress in the population that will make resorting to illegal means of bringing food to the table more enticing. For them, the prize that crime yields may outweigh the risk of being caught, given that their opportunity cost is lower. Since unemployed individuals are less involved in social activities, their probability of being either victims or perpetrators of violent crime is also higher.

Increased poverty levels may facilitate recruitment to criminal gangs as the social bonds that would normally make youngsters avoid entering the criminal world, such as well-functioning families, are being weakened. With the higher prospect and belief of making fast money from both organised as well as petty crimes, it will soon be accepted as a good thing by the communities benefitting out of it. With hopelessness, disappearing economic security, and shared disappointment, crime may offer a way in which impoverished people can obtain material goods that they cannot attain through legitimate means. Therefore, straightforward economic reasoning suggests that unemployment is an important determinant of the supply of criminal offenders and hence, the overall crime rate.

As Rajnish Hooda suggests, under such circumstances, there will be a surge in blue-collar crimes. These crimes are primarily small scale, for immediate beneficial gain to the individual or group involved in them. These crimes include narcotic production or distribution, sexual assault, theft, burglary, assault, or murder. This signifies that unemployment has an immediate and measurable effect on criminal activity by a person and that prolonged criminal activity is likely to cause an even longer stint out of the job market. Thus, the economic slowdown will not only lead to short-term negative outcomes on the labour market but can indeed produce career criminals.

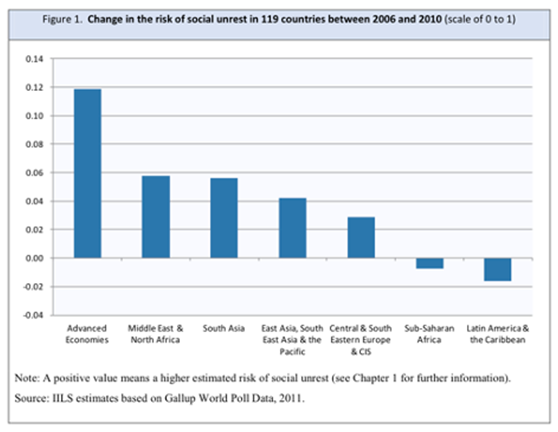

This implies that the COVID-19 pandemic will be a prelude to another crisis of unemployment and hunger with the difference that in the time to come ‘We will be no more in this together.’ The discontent over the lack of jobs and anger over perceptions that the burden of the crisis is not being shared fairly will lead to unrest in the country. Greater joblessness and increasing levels of poverty will result in an increasing level of depression that will possibly make society volatile and agitated. The decline of public trust in the state machinery might create clashes between states and citizens, eroding state capacity, driving population displacement, and heightening social tension and discrimination. This has the potential to cause debates on equity vs equality to dismantle economic barriers, protest on the streets, and increasing criminal violence and abuse in the country. The ‘World of Work’ report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) backs this correlation between increasing social unrest, unemployment, and income inequality.

Conclusion

The present situation of lockdown in India may increase unemployment rates of the country which in turn will lead to a decrease in income levels post COVID-19. This means that we may face a national or global recession. Such a situation will compound society’s problem by pushing the crime levels upward. Thus, it becomes very important for the government of India to be prepared for any such situation and take controlled measures in advance.

Anchal Chaudhary is a Governance, Policy, and Social Impact Professional in India. She is intending to explore the field of technology policy and data governance through her incoming graduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley.