What is Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)?

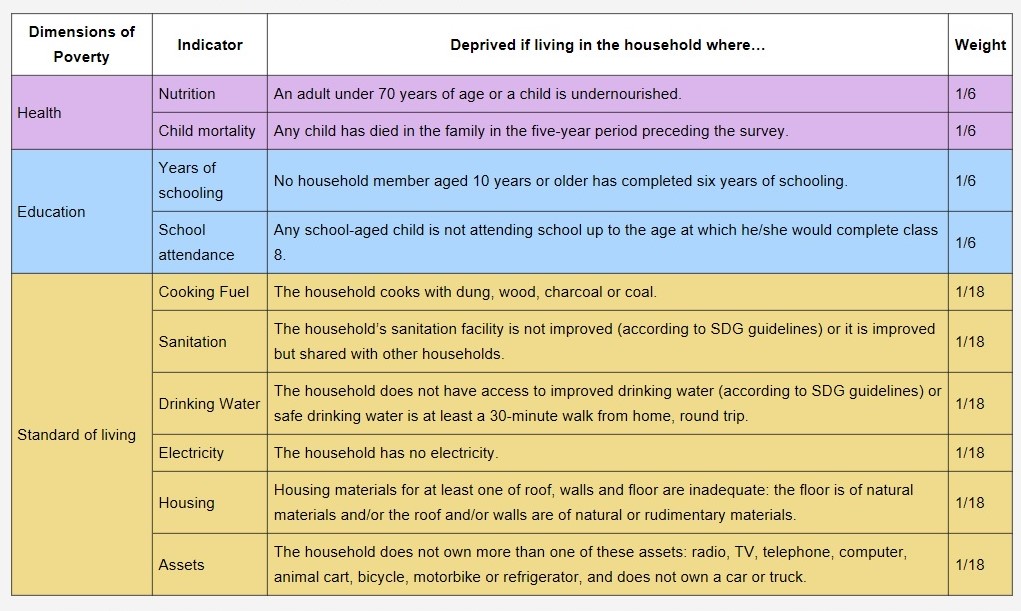

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), replaced the erstwhile Human Poverty Index as a measure of deprivation in 2010. MPI is a more holistic approach to measure deprivation than HPI since the latter focused more on the income-related aspect. MPI takes into account ten indicators across the three dimensions of health, education and standard of living. People who experience deprivation in at least one third of these weighted indicators fall into the category of multidimensionally poor. Being measured at the individual level, the measure projects itself as an important analytical tool for policy makers as well as social scientists.

Source: United Nations Development Program.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development reaffirmed the importance of multi-dimensional approaches to poverty eradication that go beyond economic deprivation. The 2018 MPI answers the call to better measure progress against Sustainable Development Goal 1 – to end poverty in all its forms; and opens a new window into how poverty – in all its dimensions – is changing.

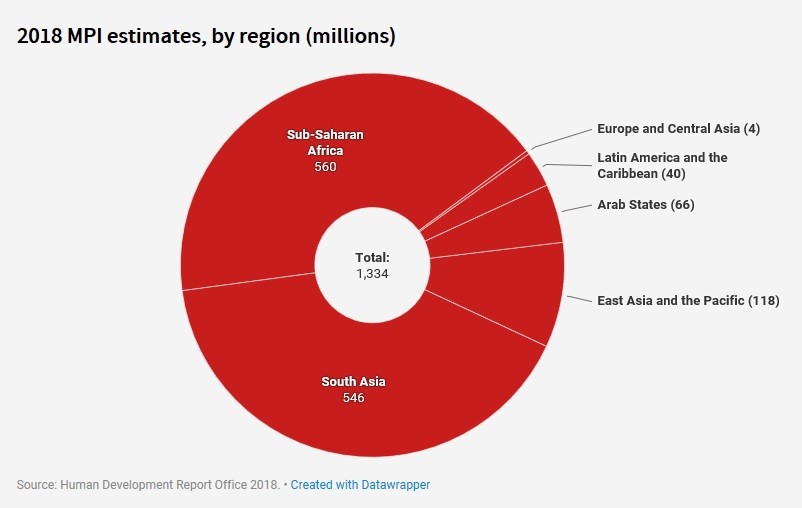

With the 2018 estimates, the MPI measures acute multidimensional deprivations in 105 countries covering 77 percent of the global population.

India’s MPI status- 271 million less poor in ten years.

In between 2005-06 and 2015-2016, the incidence of multidimensional poverty has been halved to 27.5% with most progress amongst the poorest. The absolute figure is estimated to be 271million fewer poor persons in the country, making the nation to deserve a separate chapter on the global MPI report 2018.

If one dives deeper into the chapter, then the absolute number can be seen from various perspectives. As of 2015-16, there are 364 million MPI poor population in the country, out of which 156 million are children. A massive number indeed but this is better than the corresponding figures of 2005-06, estimated at 292 million. Speaking in absolute figures, India has made quite a gain in poverty reduction.

The state-wise statistics, however, offer a very different picture. The unequal distribution, even in the case of poverty reduction, puts the burden on a handful of states. Even after the improvement since 2005-06, states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh still houses over half of the total MPI poor people of the country. While there has been progress by both categories of religion and caste groups, yet in both cases, they still have the highest number of poor as of 2015-16. The other side of the story is still grim. 27.5% of the population is MPI poor facing an average 44% of weighted deprivations. 113 million people are still in severe poverty experiencing more than 50% weighted deprivation. The nation has a long, long road ahead in poverty alleviation, despite the optimistic trend.

Is There A Sustainable Roadmap?

The report estimates that sustained efforts over the next 15 years will be necessary to continue this positive trend and alleviate gross poverty. A country with more than 70% of its population residing in rural areas, directly or indirectly dependent on agriculture needs a time-bound framework to deliver to those citizens who matter the most. Strangely enough, the agricultural community is paid the least attention to except before the polls. Do we have a long term policy (albeit time-bound) for the Indian agricultural crisis? The short term loan waiver schemes does not solve the cyclical crisis, temporary relief can no longer be the only solution. Is it possible to look at alternative agricultural practices, given a region’s own conditions?

Chained down by the rural deprivation, people migrate to the cities only to find that it is more difficult to survive. The slums in the major cities are breeding grounds of various health problems and the possibility of evacuation always looms large. The urban scenario is even worse with many homeless and little accesses to basic facilities. Most of India’s cities lack in the urban planning department resulting in highly congested urban slots while being vulnerable to natural disasters (remember the Chennai floods?). The newest feather which has been added to the cap is pollution and climate change. The urban poor are a different category altogether- one where people living in these big cities find it difficult to access basic health, education and sanitation facilities, amongst many others. Women and children bear the biggest brunt of such deprivations, the rural-urban divide having this one common thread.

India has to look inward if we truly want to progress and sustainably at that. As the nation goes to elect her 17th Lok Sabha, one can only hope that the political class has their tasks prioritized. There is a popular saying that no Indian election campaign is complete without the “ roti, kapda, makaan” call. It is 2019 and sadly, we are still aiming to provide basic necessities to the population, despite being a trillion dollar economy. India has the lowest expenditure-GDP ratios in key areas of health, education, even defence. Poverty is like a cherry on top of the cake. The society is in dire need of basics, everything else can possibly wait for the time being. While the usual development process ensures that the people will move up the income ladder but the trickle-down economics has its own fallacies and a country with 1.3 billion citizens should not be too dependent on it.

Calcutta University.