Where should the government invest if it wants to maximize India’s long-run economic growth, given fiscal and capacity constraints? This was the question posed in the 2015-16 Economic Survey. The short answer- “the highest economic returns to public investment in human capital in India lay in maternal and early-life health and nutrition interventions”. In the 70 years since independence, India has made great progress in all fields, be it economic, social or political. And yet there is much more to be achieved. The Prime Minister has recently given a clarion call towards creating a transformative movement towards “New India” by the 75th year of the country’s independence i.e. in 2022.

Since 1947, achieving food security has been a major goal of our country. When India became independent, the country faced two major nutritional problems: a threat of famine and the resultant acute starvation due to low food production and the lack of an appropriate food distribution system. The other was chronic under-nutrition due to poverty, food insecurity and inadequate food intake. Famine and starvation hit the headlines because they were acute, localized, caused profound suffering and fatalities. But low chronic food intake was a widespread silent problem leading to under-nutrition, ill health, and many more deaths than starvation. Recognizing that optimal health and nutrition were essential for human development and human resources were the engines driving national development, Article 47 of the Constitution of India states “the State shall regard raising the level of nutrition and standard of living of its people and improvement in public health among its primary duties”.

The Bengal Famine had created awareness of the need for paying priority attention to the elimination of hunger. Our Food Security Act 2013 specially mentions the need for Nutritional Security. Before we get into the details of the story, it’s important to know what the exact definition of Nutrition Security is. Various definitions have been put forward, but the one that sounds most comprehensive to me is the one by Dr. M S Swaminathan which states “physical, economic and social access to a balanced diet, clean drinking water, sanitation, and primary health care”. To articulate the concept of nutrition security, MSSRF is planning to demonstrate how agriculture, health, and nutrition can enter into a symbiotic relationship. The Farming System for Nutrition (FSN) provides a methodology for achieving such symbiotic linkages. MSSRF plans to demonstrate the power of food-based approach in some high malnutrition burden districts such as Thane in Maharashtra, Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh, Koraput in Odisha and parts of Tamil Nadu. Battling malnourishment is also one of the most effective tools to empower people left behind to participate in the growth process. An international study has ascribed the overall benefits to cost ratio to be 16:1 for low and middle-income countries.

In the early years of independence, the principal challenge was to be self-sufficient in food production. Due to the green revolution, this particular challenge was largely met. The status of the girl child and mothers is also important as their nutritional status influences the status of a child. The Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) and the BetiBachaoBetiPadhao missions by the government have been launched to tackle these very problems.

For households that value dietary diversity, being able to buy cheap cereals will free up money to purchase other foods such as milk, fruits, nuts, and perhaps eggs and meat (income effect). For households that have another dominating consumption needs, money saved by purchasing subsidized cereals may be devoted to those needs and diverted from food expenditure (substitution effect). Which effect dominates remains an empirical question.

Given the number of undergoing schemes, one may ask why is there a need for a specific mission for nutrition. A national mission for nutrition is required primarily for four reasons:

First, the current efforts are fragmented. There is a need to bring together all the relevant stakeholders on a single platform to enable a synergistic and holistic response to the issue. Second, the mission sets specific targets related to nutritional outcomes and a timeline in which these are to be achieved. This brings urgency in tackling the problem of malnutrition while demonstrating political commitment towards it. Third, the mission encompasses a targeted strategy consisting of a plan of actions and interventions. These are designed to help accelerate the improvement in nutritional outcomes. Fourth, the nutrition mission targets behavioral change through social awareness, and by creating a mass movement through a partnership between the government, the private sector and the public.

The government has approved a National Nutrition Mission with a three-year budget of Rs. 9046.17 crore primarily in response to the widespread malnutrition resulting in children with impaired cognitive abilities. The Nutrition Mission to be successful should be designed on a mission mode with symbiotic interaction between component and with a Mission Director who has the requisite authority coupled with accountability. Earlier Missions were not successful because the concept of the Mission was not fully operationalized. For example, the Nutrition Mission should have the following interactive components to make it a success:

- Overcoming undernutrition through the effective use of the provisions of the Food Security Act and also taking advantage of the enlarged food basket which includes millets in addition to rice and wheat.

- Assuring enough protein intake through increased pulses production and increased pulse production and increased consumption of milk and poultry products.

- Overcoming the hidden hunger caused by micronutrient malnutrition through the establishment of genetic gardens of biofortified plants.

- Ensuring food quality and safety through the steps for the adoption of improved post-harvest management.

The NNM has set itself a steep target of reducing stunting by 2 percent, anaemia by 3 percent and low birth weight by 2 percent every year. However, given the complexity and diversity of the issue, a routine centralized, target driven approach towards implementing the programme may not work. Instead, for the mission to succeed, a decentralized approach with a focus on the first principles- namely the 3 Fs- funds, functions, and functionaries will be critical.

On March 8, 2018, the Prime Minister launched POSHAN Abhiyaan-the Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nourishment from Jhunjhunu in Rajasthan. Through the robust use of technology, a targeted approach and convergence strive to reduce the level of stunting, under-nutrition, anaemia and low birth weight in children, as also, focus on adolescent girls, pregnant women, and lactating mothers, thus holistically addressing malnutrition. To ensure the same, all 36 states/UTs and districts will be covered in a phased manner, to be precise, 315 districts in 2017-18, 235 districts in 2018-19 and the remaining in 2019-20. Thus, POSHAN articulates its motive to provide the required convergence platform for all such schemes and thus augment a synergized approach towards Nutrition. The Very High-Speed Network (VHSN) day provides the convergence platform at the village level, for the participation of all Frontline functionaries. The Abhiyaan at the same time empowers the Frontline functionaries namely Anganwadi workers and Lady Supervisors by providing them with smartphones.

The aspect of POSHAN looks at deploying a multi-pronged approach to mobilize the masses towards creating a nutritionally aware society. The aim is to generate a Jan Andolan towards nutrition. Ministry of Women and Child development is the nodal ministry for anchoring overall implementation. Never before have so many programmes been pulled together for addressing undernutrition at a national level in India. The Prime Minister’s Office will review the progress every six months and a similar review is expected at the state level. As the NFHS-4 highlights that interstate and inter-district variability for undernutrition is very high, so every state needs to develop its Convergence Action Plan, which includes their specific constraints and bottlenecks and what they can address in short, mid and long-term.

It is very important that we put all the necessary processes in place before we start expecting miraculous changes in the undernutrition burden across the country. This Abhiyaan is going to be linked to incentives for the front-line workers like Anganwadi workers for better service delivery, for the team-based incentives for the Anganwadi workers, ASHA and ANM for achieving targets together and for early achiever states and UTs. Thus, the POSHAN Abhiyaan aims to bring all of us together, put accountability and responsibilities of all stakeholders, to help the country accomplish its desired potential in terms of its demographic dividend of 130 crores human resource.

In the last two decades, there has been a slow but steady increase in the prevalence of over-nutrition and non-communicable diseases (NCD). The population is not fully aware of the adverse health consequences of over-nutrition and tends to ignore obesity. NCDs are asymptomatic in the initial phase, only after symptoms due to complications arise do patients seek health care.

Preschool Children were recognized as the vulnerable group prone to under-nutrition and ill-health. Under-nutrition in pre-school children renders them susceptible to infections; infections aggravate under-nutrition and micro-nutrient deficiencies. Severe or repeated infections in under-nourished children if left untreated could result in death. Therefore, high priority was accorded to reducing under-nutrition in pre-school children. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) was aimed at providing food supplements for children from poor and marginalized sections to bridge the gap between requirement and actual dietary intake. Another component of ICDS programme was weighing children for early detection of growth faltering and under-nutrition and initiating appropriate management of under-nourished children.

Over the decades, there has been an improvement in the coverage under both components of ICDS but data from NFHS-4 showed that even in 2015 coverage under both the components still remains suboptimal.

Height, weight, and BMI are three parameters widely used for assessing nutritional status. Of the three, BMI Body Mass Index, which is the indicator of current energy adequacy has long been accepted as the indicator for assessment of nutritional status in adults. Analysis of data from NFHS-4 using WHO standards showed that if BMI for age is used as the criterion for under-nutrition only 18.4% of the under-five children were under-nourished and 2.6% were over-nourished.

During the 1960s, poverty, household food security and hunger were widespread among the poorer segments of the population. Poor green and yellow vegetable intake led to widespread vitamin A deficiency. The prevalence of respiratory infection and measles was higher in young children living in overcrowded households. The primary healthcare infrastructure for treating infections was poor in urban areas and non-existent in rural areas. Untreated severe infections, especially measles, in the already severely under-nourished young children, led to keratomalacia; those who survived the infections were often left with nutritional blindness. Studies carried out by the National Institute of Nutrition showed that massive dose Vitamin A (200,000 units) administered once in six months to children between one and three years of age, reduced xerophthalmia by 80 percent. Based on these findings, Massive Dose Vitamin A Supplementation (MDVAS) once every six months for 1-5-year-old children was initiated in 1970; but coverage under the programme was low. During the eighties there was a steep reduction in keratomalacia; over the next decade blindness due to vitamin, A deficiency was not reported by major hospitals. The elimination of keratomalacia was, therefore, an example of health care interventions helping in achieving nutritional goals.

Over the last three decades, there has been increasing mechanization of the transport, occupation and household work related activities. As a result, there has been a steep reduction in the physical activity and the majority of the Indians have become sedentary. The increase in over-nutrition rates was steeper between the mid-nineties and 2012. Over-nutrition rates in women were higher than over-nutrition rates in men. Women ignore such weight gain and do not seek any nutrition or health advice and incur the risk of NCD and their complications.

Data from NFHS-4 showed that with increasing age, over-nutrition rates increased as shown in the following graph.

Women ignore such weight gain and do not seek any nutrition or health advice and incur the risk of NCD and their complications. To reduce the health hazards associated with obesity, it is essential to screen men and women for over-nutrition and provide appropriate health and nutrition counselling to over-nourished persons.

Whenever the time trends in the prevalence of under- and over-nutrition are presented some in the audience feel that changes in BMI had occurred only in a small proportion of women. But over time BMI in most women has increased. As a result, the proportion of women whose BMI was below the cut-off for under-nutrition had decreased and the proportion of women whose BMI was below the cut-off for under-nutrition had decreased and the proportion of women whose BMI was above the cut-off for over-nutrition has increased.

One of the biggest changes proposed through the nutrition strategy is to orient the system towards achievements of outcomes. It will promote accountability at the ground level. This would be done through universal monitoring of parameters of the beneficiaries, and real-time tracking of the progress made. Measurement at the ground level allows stakeholders to consider which strategies are working and which aren’t and allows for quick adjustment and scaling up of successful strategies across different geographic areas. Furthermore, rankings based on improvement allow for competition between different villages, districts, and states to do better than each other and come out on top. The nutrition strategy envisages that the states, districts, and Panchayats show the largest improvement would be incentivized. The incentives could be monetary, or non-monetary, by way of recognition and awards.

Coordination between different programmes:

The schemes tackling nutrition were fragmented and were being run by different departments. To achieve coordination across those programmes, a national council has been set up under NITI Aayog with participation by the ministers from all the relevant ministries. This council will be responsible for the overall policy direction in relation to the nutrition mission and will report to the Prime Minister. The design of these institutions also promotes cooperative federalism since they include representation from 5 states on a rotation basis. States and districts would be encouraged to formulate their own nutrition plans.

Geographical convergence:

Given the wide disparities in nutritional outcomes geographically, it is logical to target districts that have been performing the worst. In parallel to another flagship programme of the government, namely the aspirational districts programme, attempts would be made to uplift the worst-performing districts. This will improve aggregate outcomes at a faster rate. The national council would also invite district collectors from 10 worst performing districts.

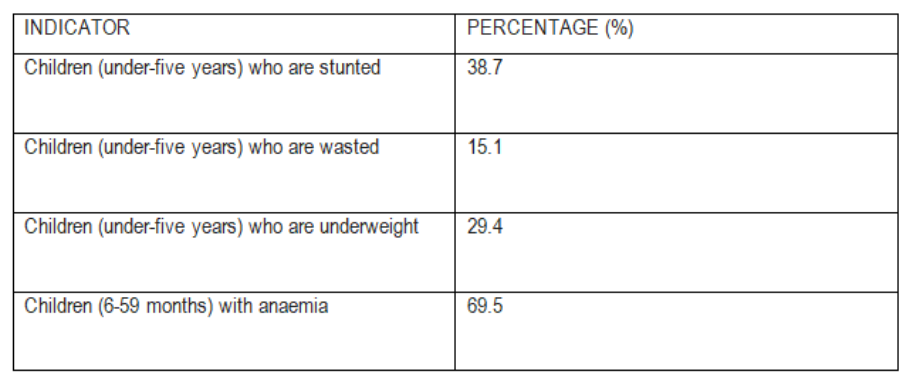

India is home to over 40 million stunted and 17 million wasted children (under-five years). Despite a marked trend of improvement in a variety of anthropometric measures of nutrition over the last 10 years, child under-nutrition rates persist as among the highest in the world. This inequality is accentuated by stark disparities across states. Possibly, the most striking visual representation of the impact that poor nutrition can have on deprivation in the brain can be found in the latest World Development Report. Focused on the global learning crisis, the report shows significant differences in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain of two infants aged 2-3-month olds- one who is stunted while another that wasn’t.

Hence, policymakers must account for two key facts:

- Direct nutrition interventions can reduce stunting only by 20 percent; indirect interventions (for example, access to Water and Sanitation) must tackle the remaining 80 percent, and,

- 50 percent of the growth failure of babies accrued by two years of age occurs in the womb owing to poor nutrition of the mother. A lack of nutrition in the first 1000 days of a child’s conception causes irreversible damage to a child’s cognitive function. Hence, there exist significant policy returns from investing in this critical stage, that is, from the period of the conception of the child of the two-year post-natal period.

Key Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSSs) with a focus on health has seen budgetary cuts over the last two years, with central allocations to the ICDS has declined almost 10 percent from Rs. 15,502 crore to Rs. 14,000 crore. AWCs require investment in vital infrastructure and Anganwadi workers (AWWs) requires monitoring to ensure that they are encouraging target groups to avail supplementary nutrition. A complimentary public intervention is the provision of school meals as part of the Midday Meal program. Field studies highlight the link between the provision of school meals and improved cognition. Furthermore, the provision of school meals has been found to lead to improved learning outcomes for children.

Policy Recommendations:

Key lessons for nutrition-specific policy interventions are as follows:

- Extend coverage of food fortification of staples:

Currently, fortification of staples is limited to the mandatory iodization of salt. However, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is in the process of formulating draft standards for the fortification of food grains which will add to the nutrient value. Additional proposals under consideration include making the double fortification of salt (with iodine and iron) and the fortification of edible oils mandatory. The standards of the hot cooked meal should also be changed to using only fortified inputs.

- Target multiple contributing factors, for example, WASH

The underlying drivers for India’s ‘hidden hunger’ challenges are complex and go beyond direct nutritional inputs. The significant push by the present government since 2014 on sanitation under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan has increased access to toilets throughout the country. However, the push for toilet construction must be combined with a strategy for behavioural change.

- Boost private sector engagement in nutrition interventions

Private sector collaboration in the form of public-private partnerships (PPP) has the potential to leverage the appropriate technology for scaling-up food fortification interventions and to develop and distribute nutrient-rich foods to improve maternal and infant nutrition. The government should facilitate PPPs in the sector that can leverage technological solutions for scaling up food fortification initiatives and complement the government’s outreach efforts through mass awareness.

Conclusion:

India faces significant challenges in harnessing long-term dividends from its young population. Her health system was built up with a focus on early detection and effective treatment of under-nutrition, infections and maternal child health problems. Most of these health problems are symptomatic and acute. Thus promoting synergy between health and nutrition services will enable the country to successfully face the nutritional challenges and achieve rapid improvement in the health and nutritional status of the population.

However, experience has shown us, implementation is usually India’s Achilles heel. The journey ahead is long and arduous, but in order to address the multidimensionality of malnutrition and the long-term effects it can have on economic and cognitive development, multiple stakeholders and local service delivery models will need to be tried in a decentralized manner.

Bidisha Bhattacharya works ScrollStack. Prior to

this she was a Consultant to the Fifteenth Finance Commission, Government of India and has worked as a Political Researcher in Prashant Kishor’s Strategic Research and Insights (SRI) team at I-PAC.

Awesome material, Thanks a lot.