What’s stopping COVID-19 vaccination from proceeding at rates adequate enough to prevent another harrowing wave? Well, a lot of things. Even as vaccination campaigns proceed around the world, countless problems persist such as supply chain disruptions, shortage of raw materials, hoarding of supplies and many more. However, one such issue that does not always get a lot of attention but is just as important is vaccine skepticism. Doubting the efficacy of vaccines or attaching conspiracy theories to it have always been a part and parcel of vaccine development. The COVID-19 pandemic has witnessed skeptics quote reasons that range from things as wild as “Bill Gates wants to put a microchip in me” to concerns about the hastened approvals of vaccines and lack of efficacy data.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the national public health agency of the US, had hailed vaccination as one of the biggest public health improvements of the last century. But for as long as this revolutionary medical discovery has saved lives, hesitancy and skepticism have existed alongside. In the nineteenth century, when Edward Jenner discovered the small pox vaccine, he was met with criticism and skepticism alike. People raised objections along multiple fronts ranging from medical and scientific to spiritual and political. Although vaccines have gone on to display their efficacy, the rampant spread of misinformation in this golden age of social media continues to pose problems. Media plays a vital role in making or breaking the public’s trust in vaccines. Social media, in particular, is often the breeding ground of unverified news. For example, in the UK, widespread claims suggesting a link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccination and autism in children was seen as a product of miscommunication and excessive consumption of mass media (Bellaby, 2003).

In the case of the COVID-19 vaccine development, one of the biggest concerns raised by skeptics has been the uncertainty surrounding scientific processes. As the pandemic ravaged on, the gravity of the situation had initially caused major manufacturers to hastily rollout vaccines and various governing bodies to quickly approve them. In the case of India, Covaxin, the country’s domestically made variant developed by Bharat Biotech, was under fire in early 2021 because its clinical trial data had not been peer-reviewed at the time of approval. This raised eyebrows and questions started surfacing online asking whether people could choose between Covaxin and Covishield, India’s domestic version of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Boyd (2020) points out that unlike most major diseases in recent history, the COVID-19 vaccine development process was closely observed and followed globally by scientists and laypersons alike. This meant that at each stage, the public witnessed in real-time the consensus on the efficacy of various preventative measures change. For example, the benefits of using face masks itself was debated back and forth for so long that it led to sections of the public remaining doubtful about its necessity. Even though it is through scientific discussions and debate that medical breakthroughs come about, the public’s increased exposure to these dynamic developments tends to cause distrust; “with fallibility comes the opportunity for skepticism” (Boyd, 2020). Along similar lines, another major reason is that ordinary citizens often turn to secondary sources (such as mass media and social media) to form their opinions when they are unable to evaluate the immense literature on vaccine development and research (Newport, 2020). This also tends to be guided by political ideology, as in the case of the US, where studies show that Republicans consuming conservative news sources were more likely to undermine COVID-19 or refuse to be vaccinated (Ritter, 2020). Moreover, there are outliers like France too, where the hesitancy towards vaccination is largely driven by past experiences of public health scandals, which has decreased the confidence in political institutions. According to a survey by YouGov and Imperial College London’s Institute of Global Health

Innovation (IGHI), 44% of the survey respondents in France said they would not take the COVID19 vaccine. Countries like Japan and Ukraine follow suit in terms of skepticism.

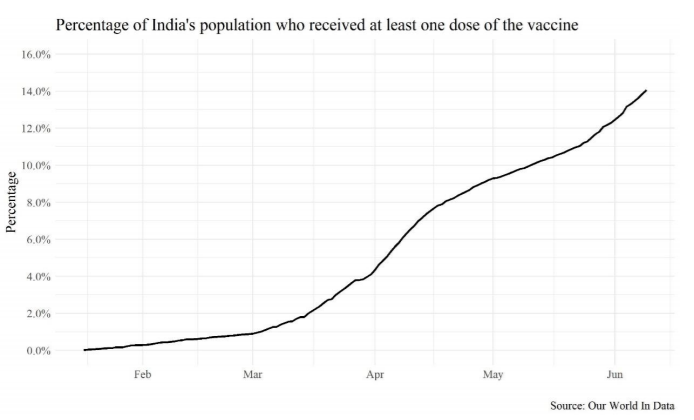

For India, the past few months have been a grim and tiring battle against both COVID-19 as well as vaccine skepticism. The union government has set ambitious goals of vaccinating one crore people per day from August, even though the current daily average is just around 30 lakhs. Estimates by India Today in May 2021 state that at the current rate, it will take 3.5 years for India to attain herd immunity, i.e., to fully vaccinate 70% of the country’s population. These numbers definitely show that India cannot afford to be skeptical. Only 3.3% of the population has been fully vaccinated so far and only 14% have received at least one dose, yet vaccine skepticism has already started to take over. A lot of factors come into play here. A sizeable proportion of Indians get their news from Twitter and other social media sites and the amorphous divide between what’s verified and what’s not paves the way for misinformation. Also, a lack of transparency and poor management practices undermines the efficacy of locally-made vaccines. By the end of March 2021, Anvisa, the official drug regulatory body of Brazil, denied Bharat Biotech (the manufacturer of India’s Covaxin) a certificate for good manufacturing practices (GMP), citing compliance issues. At this point, Covaxin was already being administered in India and had even been granted restricted emergency approval as early as January 2021, when its clinical trials were still ongoing. Brazil later allowed Bharat Biotech to export doses and issued the GMP certificate to Covaxin in June 2021, but the problem is clear: rampant mismanagement and misinformation were easily being translated to skepticism.

Interestingly, not everyone gets the opportunity to even be skeptical. Data shows that there are several economic factors that determine the extent of hesitancy towards vaccines in different countries. One such factor that drives skepticism is income-level, since it increases choices and the freedom to make them. Moreover, wealthier countries have a relatively higher exposure to social media (and hence misinformation) as well as a history of being sheltered from the harmful effects of large-scale communicable diseases. Trujillo & Motta (2021) explores economic development alongside vaccine skepticism and concludes that there is a positive relationship between the two. Other factors that drive skepticism include internet access, trust in the public health system, faith in the government, institutional management of the crisis and the history of vaccination.

While some parts of skepticism unarguably originate from a place of privilege, it is worrisome that a lot of it is born out of misinformation and mismanagement. Currently, vaccination is proceeding at alarmingly sluggish rates in most developing countries and some of the poorest countries are barely managing to get their hands on vaccine doses, even with international support. At a time when the world is busy addressing logistical and technical hurdles surrounding vaccine development, it should not be the case that something as avoidable as skepticism ends up being another nail in the coffin of mass immunization. By closely monitoring vaccine development and ensuring transparency in releasing efficacy data, governments can directly contribute to alleviating the public mistrust in vaccines. Also, at an individual level, verifying leads and reducing the consumption of unverified news would help turn the tide against skepticism.

References

Bellaby, P. (2003). Communication and miscommunication of risk: understanding UK parents’

attitudes to combined MMR vaccination. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 327(7417), 725–728.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7417.725

Bharadwaj, S. (2021, June 10). Brazil regulator grants GMP certification to Bharat Biotech’s

Covaxin facilities. Times of India. Retrieved from

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/brazil-regulator-grants-gmp-certification-to-bharatbiotechs-covaxin-facilities/articleshow/83395629.cms

Boyd, K. (2021). Beyond politics: additional factors underlying skepticism of a COVID-19

vaccine. History and philosophy of the life sciences, 43(1), 12. Retrieved from

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-021-00369-8

Ellyatt, H. (2021, January 13). France vaccine-skepticism is widespread, here’s why. CNBC.

Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/13/france-swhy-france-is-the-most-vaccineskeptical-nation-on-earth.html

Lunz Trujillo, K., & Motta, M. (2021). How Internet Access Drives Global Vaccine

Skepticism. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. Retrieved from

https://www.comminit.com/global/content/how-internet-access-drives-global-vaccine-skepticism

Newport, F. (2020, May 15). The Partisan Gap in Views of the Coronavirus. Gallup. Retrieved

from https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/311087/partisan-gap-viewscoronavirus.aspx

Praveen, S. V., Ittamalla, R., & Deepak, G. (2021). Analyzing the attitude of Indian citizens

towards COVID-19 vaccine–A text analytics study. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical

Research & Reviews, 15(2), 595-599. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7910132/

Ritter, Z. (2020, April 9). Amid Pandemic, News Attention Spikes; Media Favorability Flat.

Gallup. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/307934/amid-pandemic-newsattention-spikes-media-favorability-flat.aspx

Schmall, E. (2021, March 21). Covid-19 Is Surging in India, but Vaccinations Are Slow. The New

York Times. Retreived from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/21/world/asia/india-covid19-

vaccines-mumbai.html

Shrivastava, R. (2021, May 11). At current rate of vaccination, India will take 3.5 years to reach

herd immunity. India Today. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in/coronavirusoutbreak/story/coronavirus-current-rate-vaccination-india-years-herd-immunity-covid-1801320-

2021-05-11

Gouri is an undergraduate Economics student with a minor in Mathematics from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, University of Delhi. She has a keen interest in economics and policy research.