Indian politics since independence has had a weird fascination towards agriculture. Now, self sufficiency in grains was a major achievement of independent India, but the kind of romanticism that exists has dumbfounded me.

Truth (however harsh it may be) is, Indian politicians and voting patterns of agriculturalists in large parts of the country have caused this pitiable condition of farmers in India. The isolation and pampering of successive Indian governments which continue till date has caused the Indian farmer to fall into a vicious cycle of poverty which limits both his family’s as well as the country’s economic potential.

- Land Redistribution & Fragmenting of Holdings[1]

Pt. Nehru recognized that the average land holding size in India was too small and most farming was done at subsistence level. Hence, he initiated the co-operative farming in which smaller land holdings were to be pooled together to form larger holdings where scientific and advanced technological methods could be applied. However, This policy, didn’t really work well. Like other countries which experimented with this, the policy was a failure in most parts of the country (M.S Swaminathan, Jawaharlal Nehru and agriculture in independent India[2]). China, Vietnam and Korea moved on to a more customized community and household based farming model, which rewarded communities and households that did well, which providing no incentive for laggards. This reward-or-perish model made sure agriculture is seen just as a ‘profession’ with no form of romanticism. Those who did well were rewarded, those who didn’t had to move on to other professions.

Few states that did adopt these policies did well. Most notably, Punjab (which again has a much higher than average land holding size) which after following these foundation steps moved on to implement higher yielding seeds and other such policies under the Green Revolution, became one of the richest states in India. However, the problem was Punjab too stopped there. What was forefront of technology in 1980s is not now, lack of industrialization and an educated and skilled younger generation refusing to take up agriculture caused a sad decline in the state. While states that didn’t remained laggards. Till date land holdings show a direct correlation to the over all GDP and agricultural growth in states. States like Haryana with larger holdings have done well (Haryana today is the second richest state in per-capita terms in India if we ignore city states like Delhi and Chandigarh, and over all punches above it’s weight as a contributor to India’s GDP). On the other hand, states like Kerala, West Bengal, which were at the forefront of land reforms have had a sad state of affairs in terms of per-hectare yield. On the other hand a, large barren states like Gujarat (with over 70% land classified as arid or semi-arid), agricultural growth has been phenomenal ( decadal terms at 9.6% per annum) so much so- some claim it to be the bed rock of Modi’s Gujarat Model at its core[3].

This policy of larger land holdings corresponding to higher growth has another dimension to it as well- like this article suggests, it is way easier to set up industry in Gujarat, than Bihar[4]. For the simple reason, large number of stake holders are involved in sale and purchase of land.

While people viewing land redistribution from a social equity lens see it differently, I see it in terms of a mathematically flawed idea. Forceful distribution of land for agriculture in states such as West Bengal and Kerala did bring short-term benefits, I fail to see how no one predicted the dismal failure we can call them now. In terms of a Game theory perspective it simply achieved the following-

- Prevented those with capital and means to commercialize and boost and modernize agriculture.

- Prevented a large chunk of population from joining the industrial and other capital investment oriented work-force by making them depend on subsistence level farming.

- Prevented agricultural modernization to hit major parts of the country due to lack of means, and expertise, and sufficient holding size to afford modern methods or receive any form of positive return.

As stated earlier- WB failed to industrialize, moved from being the second richest to the 24th richest state in India, and agricultural productivity remained poor with Green revolution completely by-passing the state, operation Barga brought electoral victories to the Left-Front, however made lives more miserable in the long run. In Kerala again, unlike prevailing view- it has the largest land area under cultivation, yet agricultural growth has remained stagnant for very long[5] .

- Systematic and Periodic Subsidies, Waivers, and MSP

Unlike what politicians want us to believe, India produces more grains and food stock, than it needs. That’s right. FCI and various central and state government godowns are perennially overflowing. Large amount of produced grains and other items rot away or are eaten by pests[6].

The contrasting scenarios of record agricultural production and grinding poverty illustrate what is described as the “paradox of plenty” in the agriculture sector. India wastes around food worth approximately $14 billion each year, according to government figures.

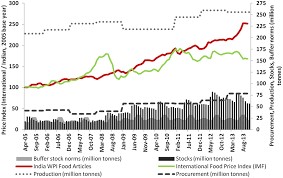

Let that sink in. $14 Billion as of 2018. Which is more than majority of state government budgets in India. The data on buffer stock vs norm from 2004–05 Economic Survey can be found here . For more recent data here is a graph (credits: Wiley online Library).

Now, for a country as poor and hungry as India, why does India produce more grain than it needs? And why does hunger persist despite that?

Answering the second question first- there is a problem in supply-chain management. Indian agricultural and distribution suffers a problem in supply chain, not in production. Lack of infrastructure – roads, transportation, ease of access to a national market, lack of market forces etc, make sure forces of supply and demand, availability and scarcity are absent.

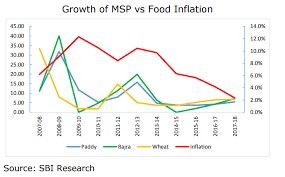

As for the first question- the simple answer is vote bank. Let’s see both the immediate and long term implications of this. MSPs push up prices and cause inflation[7] [8]. Compound this effect by poor infrastructure, this in turn affects both consumer inflation as well as wholesale inflation (the former more).

Apart from fiscal irresponsibility, this opens a host of problems- rise of short-term interest rates due to inflation targeting, loss of investment gains in real terms, eventual reduction in money supply which means growth suffers, stress on exchange rates, low real GDP growth, etc. While nominally income of farmers may increase, little or no gain comes out in real terms or in terms of purchasing patterns.

The detrimental effect on development can be understood with a comparison with China. Supply-side economics rests the three legs of the development table on – labour, capital and productivity, I have written about the latter two above, let’s look at the first one.

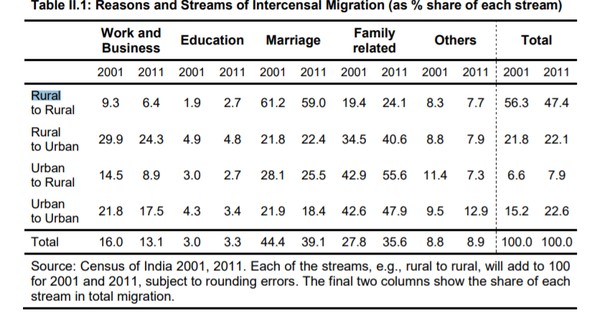

During the boom years of China, China experienced wide-spread migration to its industrial and urban centers . Large swarms of migrants who first were part of labour-intensive, low skill industries, gradually moved to more skilled industries provided a much needed boost to China. This migration peaked until China reached middle-income status and the population began aging[9]. In India, migration data isn’t available, however, as it turns out, rural to urban migration has either remained stagnant or dipped marginally in certain short time frames (maybe due to seasonal or other cohort reasons) . Inter state migration has remained alarmingly low for a country aspiring to join the ranks of middle income nations[10].

(http://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/1566.pdf)

This is alarming. Ruchir Sharma suggested in his book (Breakout Nations) nearly 10 years ago by understanding actual trends of migration in India- NREGA has prevented this migration by providing rural families subsistence level income. Subsidies obstruct market forces. As a result, despite poor conditions, large chunk of population still depends on farming.

MSPs and other rhetoric about land holdings along with red-tape has made it notoriously difficult to obtain land for industries in India[11]. The lobby makes sure any reform to this is always defeated .

NREGA isn’t the only scheme which acts detrimental to development and the natural cycle of growth. Other hand-outs like farm loan waivers, subsidies, etc, never quite let the reality hit hard. Such schemes act as the paracetamol tablet taken in hope that it’d cure one’s tuberculosis. It does push down the fever for a while, but the disease only further spreads its fangs.

- Issues with Supply Chain, Absence of Smart Farming and Lack of Micro-finance due to the above reasons

As discussed earlier, absence of a fair market which can act as a reality check and a country wide supply-chain and distribution net are absent. This severely constraints the market available to a farmer. Moreover, small land holdings, lack of capital and obsession with a few crops due to MSP, don’t really give way to smart farming according to the environmental and capital constraints. An example would be preventable droughts in states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Subsidizing crops like rice in Tamil Nadu[12] and incentives for sugar farming in Maharashtra[13] further stress out the water resources.

Smaller land holding with little or no return aren’t

particularly lucrative for few available micro-finance companies. And in recent

times the credit crunch and poor health of NBFCs[14]

which particularly were important in flow of money and credit in rural India

has only made things worse .

[1] https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/small-farm-landholdings-prevent-economies-of-scale/805043/

[2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/24092753

[3] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/et-commentary/agriculture-secret-of-modis-success/articleshow/4806513.cms?from=mdr

[4] https://www.equitymaster.com/dailyreckoning/detail.asp?date=12/08/2015&story=1&title=Why-it-is-easier-to-acquire-land-in-Gujarat–Punjab-than-Bihar-Kerala–Bengal

[5] https://www.cppr.in/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/A-Stagnant-Agriculture-in-Kerala_The-Role-of-the-State.pdf

[6] https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/food-grains-rot-india-while-millions-live-empty-stomachs

[7] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/AnnualReport/PDFs/2ECONOMIC88A5CC5468FA4639A767862F5921304A.PDF

[8] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/higher-msp-may-lead-to-inflation-as-well-as-fiscal-costs-report/articleshow/64903998.cms?from=mdr

[9] https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2016-07-19/has-china-reached-peak-urbanization

[10] https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/low-interstate-migration-is-hurting-india-s-growth-and-states-are-to-blame-119082600099_1.html

[11] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/land-acquisition-a-difficult-task-in-india-arvind-panagariya/articleshow/48306960.cms?from=mdr

[12] https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/shift-to-less-waterintensive-crops-tn-govt-tells-farmers/article9657248.ece

[13] https://www.livemint.com/Politics/XlpuWzSnQh6eWYo1fInVqI/Farm-sectors-irony-water-guzzler-cane-in-the-time-of-droug.html

[14] https://www.businesstoday.in/opinion/columns/nbfc-crisis-domino-effect-on-indian-economy-ilfs-scam-gdp-growth/story/378109.html

Pratyush is a student of Vellore Institute of Technology and a self-taught Economics Enthusiast.