The decision taken by the Central Bank on Thursday, 7th of February not only did surprise economists but market watchers as well. Whereas the unanimous decision of changing the monetary policy stance from ‘calibrated tightening’ to ‘neutral’ seemed plausible, the cutting of the repurchase rate by 25 basis points didn’t quite seem a sine qua non. While Headline Inflation, led by Food Inflation has been in the safe zone, continuing high levels of core inflation had led to the expectation that the RBI might stop short of cutting rates and restrict itself to a change in the stance of the economy. The rate cut, therefore, took us a bit by surprise.

For all those arguing over the impact of this rate cut more on production or inflation, a slight reality check. Historically, it has always been observed that Central Bank policy actions have had a much more immediate impact on Inflation than on Production: let’s understand WHY?

To begin with, let us recall a very important factor and keep that in mind as we proceed along the logic: while lending rate cuts depend on the efficiency of the Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism, there is another area where monetary policy has a quick impact- THE MONEY SUPPLY.

When the Central Bank (in our case, RBI), reduces policy rates, the first thing Commercial Banks (like SBI, ICICI etc) do is reduce their interest rates on deposits. REASON? Interests paid on deposits are their cost and they would be too glad to reduce it whenever the opportunity knocks.

Once the interest rates on the deposits reduce, people will be less inclined to keep their money in deposits as rates of return are now lower. Hence the additional money that they will be keeping for themselves will transform into nothing else but increased Consumption in the short-run. This will increase Demand. Now, increasing supply of consumption goods is hardly possible in the short-run which increases the prices of the commodities and thereby steps in the Elephant in the Room-INFLATION.

While it did seem a welcoming move for providing a bigger push forward to the demand side of Real estate and making loans cheaper, the policy move did seem a bit premature. Here’s why

Indeed inflation is unlikely to hit 4% anytime soon, but as per the current economic scenario, the underlying pressure still remains upward. On one hand, while high core inflation, running at about 6% in the current financial year clearly reflects elevated inflation expectations, loose fiscal policy and a weak currency step in as other factors likely to push prices up going forward.

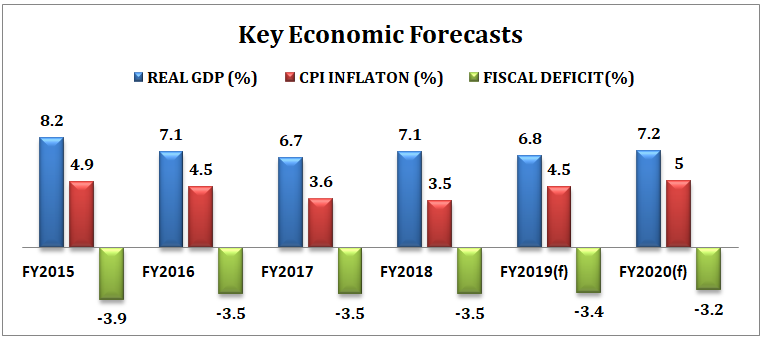

Source: Bloomberg estimates

To add on to this, government bonds gained and the Indian rupee weakened in a knee-jerk reaction to the RBI’s decision.

Bonds might not be able to provide relief for long as the persisting wide fiscal deficit would continue to pressure yields higher. The INR7.04 trillion government borrowing plan for FY2020 announced in the budget a week ago represents an over 30% increase from the revised INR 5.35 trillion borrowing in the current year. This will not only put pressure on the borrowing costs but would also cause a significant crowding out of private investment, thereby weighing on GDP growth.

The answer to the question we need to look out for presently is why did we need a loose monetary policy when the fiscal policy was already supporting growth well above 7%?

Bidisha Bhattacharya works ScrollStack. Prior to

this she was a Consultant to the Fifteenth Finance Commission, Government of India and has worked as a Political Researcher in Prashant Kishor’s Strategic Research and Insights (SRI) team at I-PAC.

As states have their borrowing programs it would be useful to estimate total borrowings by Union Government ,States and Public Sector .and see the trend. Debt to GSDP proportion in most states and Public Sector borrowing has accelerated in recent years.

Sure, Sir. Will definitely do the calculation. Thank you so much for your valuable feedback.