Sri Lanka is going through its worst economic crisis, further causing political instability in the island nation. As of 4th April, an “emergency” has been declared, the Sri Lankan government is in disarray, the opposition looking for vengeance, people suffering and rioting on the streets, and its economic institutions trying to make sense of what has happened, what is happening, and what should be done.

Sri Lanka is facing a run on its currency with a shortage of foreign exchange to repay its liabilities. Further fueled by the losses in the tourism industry and decreasing remittances, Sri Lanka’s inability to import fuel is contributing to long power cuts, ultimately resulting in soaring inflation. The economic impact of 2 years of the COVID pandemic and the ongoing Ukraine-Russia Crisis might have triggered this economic catastrophe, but its roots go back to decade-long economic mismanagement focused on populism and short-sighted strategic decision making. A closer look into Sri Lanka’s fiscal and monetary policies over the last decade makes it very clear that for the past few years, the Sri Lankan economy has been living on borrowed time (and money, as it so happened).

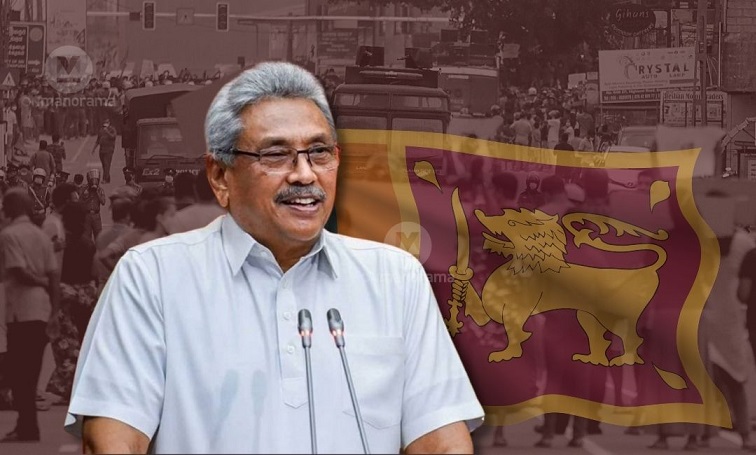

There is an inherent danger of economic mismanagement in populism, and the ongoing Sri Lankan crisis proves the argument. Gotayba Rajapaksa’s presidency is marked by successive disastrous economic policy decisions ranging from tax cuts, freebies, and anti-modern policies such as the ban on chemical fertilizers, so on and so forth. As of today, the total public debt in Sri Lanka stands at 119% of its GDP. Inflation is nearing 20% (although reports suggest it may be as high as 45%). Its forex reserves stand at USD 2.3 billion, with USD 4 billion in debt payments due this year.

Sri Lanka has been a heavily service-oriented economy (thanks to tourism and cargo hubs). In any service sector-dominated economy, the dependency on external elements (such as foreign tourists, trade, etc.) plays a major role in revenue generation. Hence, service sector-dominated economies need to be extra careful about their “deficit financing” (especially in times of geopolitical distress) as they are unlikely to pay for the debt through domestic economic production. But populist agendas rarely come with such foresight, as they are more concerned with getting through one election after another.

Heavy government spending followed by low domestic production requires heavy borrowings from external agencies. Over the last decade, Sri Lanka has borrowed heavily from foreign lenders to fund its political promises. Sri Lankan government agencies and some analysts are pointing fingers at the last 3 years of both natural and manmade catastrophes such as heavy monsoons, terror attacks, and the pandemic for causing this crisis. But it is a foul cry. This is a structural crisis caused by populist economic agendas and fiscal mismanagement. And it’s high time for other developing economies to take this as a warning against anti-modern, uneconomical policy (political) agendas.

Anatomy of the Crisis:

The 2019 Asian Development Bank Report highlighted Sri Lanka as a classic twin deficit economy. A “Twin Deficit” refers to higher national expenditure than income, coupled with inadequate production of tradable goods. This fundamental economic imbalance has further led to high levels of debt, a heavy reliance on foreign capital inflows, a steady depreciation of its currency, and high-interest rates. Also, historically, Sri Lanka has faced balance of payment (BoP) crises at regular intervals, with as many as 15 arrangements with the IMF between 1952 and 2022. This further strengthens the case for fiscal consolidation and responsibility.

The documentary evidence from the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and the IMF made it clear that this current economic crisis is a result of economic mismanagement by successive governments. In 2019, Sri Lanka’s ailing economy suffered a severe blow due to an Easter Sunday attack. Following that, in November 2019, newly elected President Rajapaksa announced his “Tax Cuts” as he had promised during election campaigning. This popular political move may have provided temporary relief to Sri Lankan citizens, but it first resulted in the downgrading of credit ratings, followed by the loss of access to international financial markets. further added to the ever-increasing national debt, causing higher inflation and a devaluation of its currency.

On the geopolitical landscape, Sri Lanka holds a strategic position in the Indian Ocean and its growing proximity to China as part of the Belt Road Initiative gives it strategic leverage. Despite this, Sri Lankan leaders lacked the foresight to exploit such leverage for economic growth and prosperity. Instead, the Sri Lankan government used its initial leverage to borrow more and more from China and India to fund its populist agendas, leaving them strapped for both cash and leverage. Over the last decade, Sri Lanka has fallen victim to China’s debt-trap diplomacy. For cash-strapped countries such as Sri Lanka, the availability of easy money at a higher interest rate was a lucrative offer garbed under the facade of infrastructure development. But as the country defaulted on its repayment, Chinese institutions forced Colombo to hand over control of some of these projects. The point of this argument is not only to highlight China’s debt-trap modus operandi but also to elaborate that no amount of funds and support can help a mismanaged economy running on populist policy agendas.

Along with fiscal mismanagement and debt-trapping, the anti-modern political economy outlook of the Sri Lankan government has made matters even worse. In 2020, President Rajapaksa imposed a total ban on agrochemical-based fertilizers, with only organic farming permitted in Sri Lanka. While banning chemical fertilizers and boosters in agriculture is an anti-modern idea, doing it during the pandemic was an outright stupid and dangerous idea. Although the government realized its error and revoked the order a few months later, the agriculture industry had lost nearly half of its production capacity by that time. This forced the government to import even the most basic staples, including rice, at the height of the economic decline, further contributing to the ongoing crisis.

The Way Ahead:

Sri Lankan economy is in the doldrums and its people are suffering due to inflation, lack of food, fuel, and power. There is an impending political crisis that could make the matters worse. The Sri Lankan government is in talks with its global allies for rescue packages. India has an extended credit facility to Sri Lanka and is also exporting food and necessary supplies with other global actors chipping in as well. In all probability, a bail-out is coming. Still, a few long hard months awaits the fate of Sri Lankan citizen. It is high time for the Sri Lankan public discourse to understand the base causes of this misery. Fiscal responsibility is the need for an hour. No policy measures can succeed unless Sri Lankan institutions start addressing the populist agendas causing crises every ten years.

The government also needs to be cautious with its external borrowings. Heavy borrowings create more debt. And when one borrows more to pay off the deficit, it starts obstructing the effectiveness of monetary policy and exchange rate management. In a crisis such as this, there are no quick fixes. Steady structural reforms are the only sustainable way out. As argued by the Asian Development Bank 2019 report, “fiscal policy efforts need to be supported by reforms to generate nondebt-creating foreign currency inflows to stabilize the external sector and assist in building up a buffer stock of official foreign exchange reserves.”

The Sri Lankan crisis is also a reminder of the perils of populism. It is as much a responsibility of the people and the civil society as it is of the government to ensure that political frenzy and opportunism do not lead to anti-modern, uneconomical policy (political) agendas and economic mismanagement.

Atharv Desai heads Academic and Research Center at COVINTS. Atharv studied International Political Economy at the University of Nottingham.