COVID19 pandemic is not merely a health hazard but a catastrophic disaster that surpasses every aspect social, political, economic, environmental and geopolitical. A close interdependence between these several aspects exacerbates its impact. For instance, to curb the spread of the virus there has been a cessation of economic activities, closed trade borders, imposition of domestic and international travel restrictions. This effort to contain the spread has severe ramifications on the prevailing social order, the economic development, unemployment rate, poverty rate, inequality level, international trade relations, geopolitical relationships, giving COVID19 the form of a catastrophic disaster. The pandemic has exposed the inefficiencies prevalent in the present socio-economic system and calls for a paradigm shift in the present system which is resistant towards any such future event.

Impact of COVID19 on international trade and GVCs

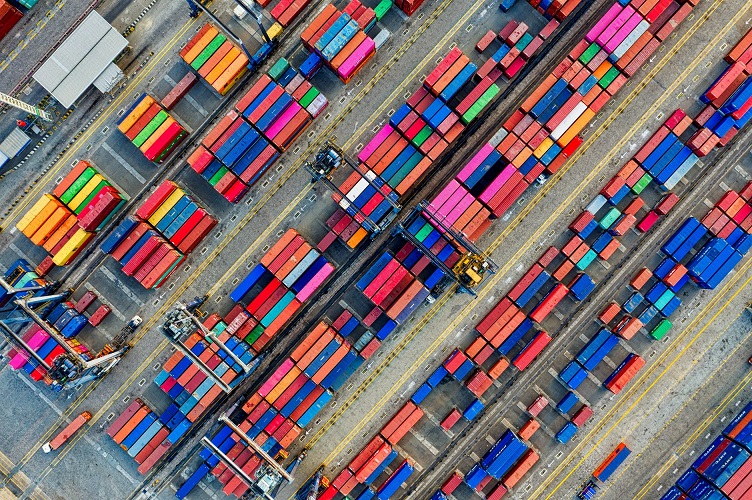

Presently, more than a third of the world’s population is in some kind of restriction resulting in an economic cessation with the global economy being entered into a recession[1]. The economic adversaries arising out of the pandemic are likely to be accentuated due to the highly fragmented and complex network of Global Value Chains (GVCs) operating across different countries and companies. The past few decades have undergone a substantial increase in the GVCs on the back of a liberalized trade regime. This has enabled companies to slice their value chains and to relocate or outsource the production activity to the minimum cost production location. As a result of this, the trade in intermediate goods and services now account for about two-thirds of the total international trade[2].

The more fragmented the GVCs across different countries and companies, the wider the negative impact of the lockdown on the economic activity, higher the cross country and regional contagion effect and greater the economic uncertainties emanating out of the asymmetric spread of the virus across different countries and regions. This is evident from China’s case. China enforced a lockdown (started from late January and continued till first week of April) in atleast 16 cities which was later followed by an imposition of trade and travel restrictions with China by other countries. This plummeted manufacturing in China, severely affecting the supply and demand of intermediate goods and services from China to the companies located in different countries closely integrated into a vast GVC network of forward and backward linkages. This impact on supply shortages is likely to have been aggravated due to a just in time management of inventories approach followed by companies in a GVC network. This also affected the economic activities in several developing countries acting as a supplier of basic raw material to China.

Now, China has reported control over the virus and has resumed its’ economic activity (physical distancing restrictions still imposed) but the virus has now spread to different parts of the world. As of April 28, 2020, there were over 3 million COVID19 infected people with over 211 thousand reported deaths and over 922 thousand reported recoveries globally[3]. This has resulted into lockdown in other countries. In this scenario where there is a lack of demand in other virus hit countries, even China cannot maintain its pre-COVID19 trade and production levels. The impact is highly uncertain and prolonged due to an asymmetric spread of the virus across countries.

The production cuts and an economic slowdown is likely to be aggravated well beyond the post-recovery phase of the virus because of a demand slowdown, an immediate fallout of this sudden COVID19-related economic shock. Amidst lack of business operations, several medium and small enterprises will go bankrupt resulting in mass layoffs and unemployment. This is evident from the unemployment claims filed in US peaking at about 26 million in just five weeks of the lockdown[4]. It entails a rundown on household savings and a greater reliance on government financial assistance. This will also be accompanied by a postponement of demand for discretionary goods thereby further delaying the recovery process. This demand deacceleration will have a direct contagion effect on other countries closely integrated through a complex and vast GVC network spread across different countries. As a result, negative multiplier effects will set in creating a vicious circle of slowdown.

COVID19 to accelerate the anti-free trade drive

The pandemic has come at a time when globally there has been a growing concern towards high unemployment, skyrocketing inequality, depressed demand, environmental concerns emanating from a liberalized trade regime giving rise to a wave of protectionism. There has been a surge in the imposition of non-tariff trade barriers by countries to promote domestic production especially since the global financial crisis[5]. However, the past few years have seen an open resentment against free trade materializing into an explicit increase in import tariffs and calling off, postponement or renegotiation of FTAs between countries with wider populist support. This anti-free trade drive is accompanied by greater polarization with diverging policy interests. On one hand, there are proponents of free trade – companies which have outsourced production operations abroad and benefit by lower trade barriers and on the other hand there are low-skilled workers who losses from greater trade liberalization[6].

The pandemic has not only raised concerns among the policymakers about the adverse consequences of a highly integrated and complex trade relations but has also triggered higher populist demand for decoupling the economy from China from fear of any future disease transmission. There has already been an imposition of cross-border trade restrictions. The upliftment of these restrictions will though happen in a phased manner but some restrictions may continue to stay and countries may use it for promoting domestic production especially at a time when domestic unemployment rate would be very high. It would be difficult for the countries to reinforce and sustain the pre-pandemic trade relations, when WTO Dispute Settlement Body has become dysfunctional which uptil now was acting as a lever for promoting trade. This may result in over-enforcement of retaliatory measures by countries thereby further fueling the anti free trade drive[7].

The international trade repercussions arising out of the pandemic are likely to be widespread because of a complete suspension of cross-border trade and high uncertainties. The medium-term impact of the pandemic on international trade and the degree of efficacy of anti-free trade measures depends on the ability of the domestic producers and service providers to scale up operations. Moreover, it depends on the duration of the slowdown and the extent and kind of government intervention adopted to contain the negative downward spiral.

It is impossible for countries to completely isolate themselves from the international community and there will still be continued reliance for intermediate inputs even when one resorts to protectionism. However, there will be an increasing consensus to reduce the complex interdependence, a byproduct of a highly fragmented GVC network. The future trading relations will be characterized by higher regional interdependence and strengthening of the domestic economy to withstand such catastrophic events which may now become a recurring phenomenon because of rising environmental and health concerns, a fallout of globalization.

1 Kaplan, J., Lauren F. and Morgan M. (2020). A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown. Business Insider article.

2 Johnson, R. & Noguera, G. (2012). Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added. Journal of International Economics, 86(2), 224-236.

3 Worldometer’s COVID19 data

4 Rushe, D. and Amanda H. (2020). US unemployment applications reach over 26m as states struggle to keep up. The Guardian article.

5 Yalchin, E., Gabriel F., Luisa K. (2017). Hidden Protectionism: Non-Tariff Barriers and Implications for International Trade. Ifo Institute.

6 Van Assche, A., and Byron G. (2019). Global Value Chains and the fragmentation of trade policy coalitions. Transnational Corporations, Volume 26, 2019, Number 1.

7 Hedge, V. (2019). As WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body Dies a Dysfunctional Death, What comes next?. The Wire article.

Vamika Goel is a Post-Graduate in Economics from Centre for Economic Studies & Planning, JNU. She has worked as Research Associate at Economic Affairs Division, FICCI. Her interest lies in Indian Economy, International Trade, Agriculture Economics and Sustainable Development.